1974

Cloyd Davis and I were bumping up the long haul into Pigeon Water, in North-eastern Utah, when the deer suddenly appeared. There had been nothing but rocks and sage on the hillside a moment before, but suddenly there they were, running heads up and alert. A big doe led two smaller ones, and a middling buck ate their dust, his nose full of doe scent and his neck swollen with rut. Cloyd and I had been waiting for just such a sight for the previous four days, our appetite whetted by the big buck that Terry Scholes had put down two days before with his 50 caliber ‘Poor Boy’.

I instinctively slammed on the brakes, careening to a stop as the deer turned into the narrow ravine we had been crawling along, crossed in front of us and bounded up the hill to our left. They were headed for a big clump of Quaking Aspen about 100 yards up the hill, the first cover in sight.

Cloyd was out of the truck before I could get it stopped, his long-barreled fullstock percussion rifle ready. He ran a few steps in front of the truck, fumbled on a cap and pulled trigger just as the buck disappeared into the Quakies. The crack of his 50 was followed by a solid thump as the bullet struck home. The buck went down, rolling nose over teakettle, staggered to his feet and burst into a thumping run, headed back the way he had come.

|

| A fine original example of a ‘French’ flintlock, the ultimate amalgamation of all the flint using locks that preceeded it, combining all their best features in a small, efficient form. It was in use as early as 1625 and is the form that everyone recognizes and uses now. |

I hadn’t been idle in the meantime. I had managed to stop the old truck without tipping it over, slammed on the emergency brake, grabbed my rifle and tumbled out. I flipped open the frizzen, dumped in a panfull of priming powder, and picked up the deer just as Cloyd’s shot knocked over the buck.

I was thumbing the frizzen closed and cocking the hammer just as the buck jumped up and took off, running near as fast as if he hadn’t been hit at all. It seemed instinctive to slip to one knee, lining up the sights on the running buck, now about 125 yards away. I squeezed the trigger, then squeezed some more, and it seemed like forever that the rifle wouldn’t go off. It suddenly struck me that I hadn’t set the rear trigger of the DST in the excitement, and the buck continued his humped up run as I reached for the rear trigger, my heart in my mouth and my hoped for a clean shot sagging into my boots.

Have you ever noticed how you can feel the whole sum of your knowledge and experience on a subject when catastrophe threatens. This is what I experienced when my mind finally figured out the slackness in that trigger. I remembered, in an instantaneous burst of memory, the days when I used to glory in the beauty of hunting with ANY muzzleloading rifle, not only my beloved flintlock, comparing it with the lackluster experience of the more modern cartridge. I can suddenly feel again that teenage hankering that I once had to actually possess a working flintlock, a feeling even more intense than the one that led to acquire my first percussion rifle and take the long leap into muzzleloading.

I remember finally saving enough bucks to buy a honest to gosh flintlock from Miller Bedford, whom most of you won’t remember,. It was an original French pistol lock. It had a few replaced parts, but it sparked well and it pleased me immensely. Somehow I built it into a 32 caliber fullstock rifle and later managed to get me and rifle into a patch of cottontail rabbits. It was fall time in my cold northern Utah country, not quite cold enough to freeze the spit patch as I rammed round ball and patch down the barrel, but cold enough to give me the shakes. At least I shook every time that little rifle went off. I remember wondering why anybody should flinch that bad just because of a little fire in the face. At least there were many rabbits and it gave me lots of practice.

Of course , it’s fun now to watch a new flintlock shooter go through this peculiar agony, him expecting the flash to singe his eyelashes and spot his pristine brow. It‘s really great to demonstrate how steady I am, now that 40,000 shots are under the bridge, and how adept my reflexes are at holding breath, squeezing trigger, lining sights, and steadily waiting for all that commotion that happens before a ball is free of the barrel and on its way to a bulls-eye.

|

| Charley Winn with a Doc built copy of a fine side by side double Penn-Ky rifle originally by Christian Beck, 45 caliber, one side rifled, one side smooth. |

Now, this is what flintlock shooting is all about. It is on follow through that all the other principles of flintlocking depend. It boils down to the fact that a flintlock shooter can never quite predict the exact moment when his rifle will go bang. The reason being that the time lag between the fall of the cock and the firing of the gun is quite variable. It is this variable lag time, present even in the quickest of flintlocks, that comes as a consternating surprise, requiring considerable practice and concentration to overcome.

Now, flintlocking at your favorite shoot, playing the target game, is not the same as pursuing game in the field. The flintlocker on the target line is shooting steadily, never allowing his priming to sit in the pan for longer than just the few seconds it takes him to prime, raise his rifle and fire. There is much less chance for moisture to penetrate the priming, a terrible problem if it’s raining or snowing, and a miserable problem even on a moist day in a humid climate.

I lived in Virginia long enough to find out what a problem moist priming could be. We lived right close to tide-water and the air was sometimes so boggy you could clap your hands and it would rain on your shoes. Good barrel iron rusted so fast in that country that a hunter often had to run an oiled patch down his barrel after loading his first shot of the day, because if he didn’t get it shot off by noon all he’d have in the evening was a streak of rust. Priming would turn into black goo in the pan if not changed often, and the pan had to be thoroughly wiped with every change of priming so that moisture in the pan wouldn’t wet the new priming before the pan was closed.

Squirrel hunting was a natural in those tall woods. So many big trees around that it blighted a man’s vision, couldn’t see the horizon, let alone the sun come up some days in the deep woods. And if there was any moisture in those high leaves, it was sure to drip straight into the pan. I soon learned to hump over my lock as I loaded or changed priming. I soon learned what a ‘cow’s knee’ was, too, except we couldn’t usually sacrifice a cow and had to make our protective flintlock covers out of any old piece of rawhide that came along. One of my crazy friends designed a bib with an oilskin cover just special for keeping the rain off, it protected his shirtfront too. I even learned to take special care to wipe off the underside of the frizzen, that part that forms the roof of the pan, and which touches the priming first when the pan is filled too full. I once spent all day hunting in a little drizzle, re-priming repeatedly and yet failing to. get a flash, before I found out that pans have roofs as well as bottoms and filling a pan without wiping its roof is inviting a misfire.

That’s good advice even in dry country, but for a different reason; fine black priming powder compacts easily, and a hard block of priming is harder to start burning than a fluffy, dry charge rattling around loose in the pan.

More sooner than later, I found out that all flint guns are not built alike, many being downright inferior. My first few touch-holes are a good example. I had seen a few original rifles before I finally acquired a flinter, all of them early American types but none ascribable to any “school” of rifle building except bad. All the touchholes were plain straight holes drilled directly from the outside to the inside of the barrel, You can guess that my first touch-hole looked exactly the same and produced the same results; a long if not prolonged “Phtttttt” between the flash in the pan and the shot. This was not in the least conducive to exceptional accuracy. Later in that decade, I finally ran into a fine English rifle with platinum lined touch-holes, based on the system first engineered by Nock, an Englishman of genius who bored out his touch-holes, tapped an appropriate thread and screwed in a fancy counter-bored liner. Loading this particular piece was a revelation. The external touch-hole was small but a grain of powder could be seen protruding from the touch-hole after throwing the main charge. The trigger pull produced an instantaneous shot, as good as any percussion and darned near as good as a modern rifle, For those that can’t afford platinum, counter-bored touch-holes made of Ampco metal (a beryllium bearing bronze) or stainless steel are commonly available now from muzzleloading supply houses, but for years they had to be made from Ampco nipples before the manufacturers caught on.

Even with the advantage of a counterbored screw-in liner, the touch-hole still has to go in the right place. That’s in the middle of the pan, on the line between the top of the pan and the bottom of the frizzen. Any lower than that and the chances of the priming having to take time to burn down far enough to finally flash through the touch-hole is increased. What I really want is for the priming’s top surface to lay in such a position as to flash the first bit of its fire across to the empty touch-hole and through it to the main charge without having to slow down because of touch-hole constriction or piled up priming in front of it.

I am reminded of the time in 1974 that I was standing in front of a big pine tree in the Uintah Wilderness Area during the local muzzleloading deer season. I was pretty well snuggled into that tree, hoping it would hide me pretty well, and a game trail meandered right past my feet. The day was pretty and the air pristine and cool and I was in my glory, as only a man can be when lost in the wilderness. I had not seen another hunter the day through, except the hunter I started out with, and the birds were twittering and the wind breathed through the trees as I watched the blowdown to my front. I had never failed to see deer in this particular area as the feed was especially luxurient, growing especially well where the big trees had been destroyed and sunlight let through to the ground. Second growth grew high in this area, and the mule deer just loved it. So did I.

I \vas just being quiet, enjoying the day, when the sudden thumping of hurrying feet told my senses that something was coming fast. You know how quickly that can happen. Your ears pick up the sound and before you can think, your instincts have taken over and your body is ready for action. I suddenly found myself on one knee, with rifle up, cocked and DST set, ready for what I hoped would be a big grey buck ghosting through the brush.

The rifle I was carrying wasn’t really worthy of note except that it had a particularly good old English “Sea Service” pistol lock on it, with DST and fancy touch-hole. It was also possessed of a 58 caliber Bill Large barrel and was full-stocked in the contemporary “flintlock Hawken” style that had cropped up in the prior 25 years. I had been shooting and hunting with the rifle since I built it in Alaska some years before, and, most important, I had a lot of confidence in it. It was loaded with a .562 ball over140 grains of FFg black powder, old Dupont stuff that I saved for special occasions like. hunting in the High Uintahs.

“Ol’Skunkum”, the 58 caliber Bill large barreled fullstock flintlock Hawken copy with original ‘Sea Service’ pistol lock.

“Ol’Skunkum”, the 58 caliber Bill large barreled fullstock flintlock Hawken copy with original ‘Sea Service’ pistol lock.

I was tensed and ready for that big buck when a burly chocolate form hurtled into view, only a few yards to my front and coming fast down the trail I was standing in. It was a bear, head down and grunting in his hurry. All I had time to do was pull the trigger, which I instinctively did, sights lined up on the bear’s shoulder at 15-20 feet. The rifle fired quick as a wink, and the bruin went down, thankfully jumping to his feet and galloping off in the opposite direction. When he ran into a tree after only a few steps and staggered off into the, brush. I knew he was hard hit. Sure enough, I found him dead just a few steps into the brush.

My point is not that I was so brave or courageous as to stand in front of a charging bear and accept the odds of hurt or injury in the effort to stop the bear. That was definitely not the case. In the first place, Utah’s black bear aren’t all that aggressive, or all that dangerous, although I’d hate to be bitten by one, even by accident. This poor bruin didn’t even know that I was around, at least I didn’t think so. The point is that the gun had proven itself so well, because of its superior design and materials, that I had no instinctive bias against using it in a somewhat tight situation. Besides I’m really a big coward, and 20 minutes after the bear was down and dead I was still shaking.

Of course, it wasn’t just the magic touch-hole that got the ticklish shot off just right. It was a few other things too; like the priming sitting in the pan just right. A hunter can’t be constantly changing his priming, but he has to constantly keep it in mind, and check on it often enough to know just exactly what it’s doing. I’m ‘reminded of a little deer that I stalked in Colorado some years ago. I had been hunting Colorado’s high mountain country. A great hunt, but that’s all it was. We hardly saw a thing and didn’t get a shot, except that ‘Liver Eatin’ Sweeney managed to connect. He was the only one. (We call him that because he hates liver so bad). I was driving home along Hiway 40 when I spotted a herd of mulies just off the highway just at dusk. They were standing right out in the open, sagebrush up to their knees, and the wind howling about their ears.

|

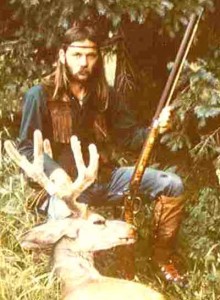

| Liver Eatin’ Sweeney and buck. He over-nighted under a tree, shivering in the cold of the Colorado mountains, to get this buck early the next morning. |

I was about halfway between Bluebell and Elk Springs when I saw the deer. If you have ever been out in that desolate part of world, you’d soon find that the wind never stops blowing. It might slow down just a little once in a bit, but it never stops. On this day, it wasn’t even slowing. I made sure I was seeing right, then pulled over at the top of the next rise.

Using the cover of the hill, I got to windward. There really wasn’t much cover in that sere country. When I made it over the low rise, there was only one buck in view, about 600 yards up wind. I didn’t know where the others had gone, but didn’t care either. This was my last day to hunt and the last deer I would probably see as the light was failing fast. Besides I was awful hungry for venison liver. I could near taste it.

The ridiculous thing was that both the small buck and I were flat out in the open with not enough cover to hide a jack rabbit in sight. So I just walked towards him, standing straight up, gun ready. Every time he lifted his head for a look see, I would stop and hold the position I was in, sometimes with a foot in the air. When he would duck his head to feed, I’d hurry ahead a step or two. It soon became a fascinating game, seeing how close I could come without spooking him. I was on hands and knees by then, scrabbling around in the cactus, the wind still howling past. Luckily I thought about checking the priming one last time, and there wasn’t any in the pan. The wind had blown it all out.

Mind you, this was a very nice rifle I was carrying. It sported a professionally: made Siler flintlock, a fancy counter-bored touch-hole and an expensive Green River barrel in 54 caliber. The touch-hole had been carefully installed in the right place and the flint sharpened before the stalk even started. Everything was prime for the shot except the priming. I’d even gone to the trouble of hand fitting the frizzen bottom to the top face of the pan, coating the edges with black then filing away metal where the black touched the frizzen lid bottom. I thought that I had a wind proof pan, but that Colorado Zephyr still blew the priming out. Even as I turned my back to the wind in order fill the pan, it occurred to me that the wind still might blow the prime out before a spark could get to it, or even blow the sparks away.I tried it anyway, pulling trigger on the little buck as he was looking at me from 20 yards. The lock flashed and the rifle fired just as it was meant to, the 220 grain bullet propelled by 140 gr FFg black powder about breaking him in half on impact. At least there wasn’t any suffering on his part, and I ate liver that night, with onions, and in the privacy of my own kitchen.

The flintlock hunter needs to check his priming often, at least looking at it, making sure there’s not too little or too much and that the flash-hole isn’t packed. He needs to be in the habit of jigging his rifle or shotgun to the pan side just before a shot in an attempt to settle the priming more to the outside of the pan so it won’t plug up the touch-hole and slow down the flash. This is especially true of the flintlock shotgun.

|

| Greg Roberts is just about to pop that big rooster with a best quality Staudenmeyer double flintlock fowler. It’s as handy and quick as any modernshotgun. |

1’m lucky enough to own and shoot an original English 16 gage flintlock double fowler, one of London’s best. It was made by Staudenmeyer about 1810 and still shoots like new. It has all the amenities, including water-proof locks and self-priming pans, platinum counter-bored touch-holes, superb flintlocks and the most consistent ignition time of any flint gun I’ve ever owned. I’ve broken 23 of 25 on skeet with it on at least one lucky occasion, and have managed to kill hundreds of assorted birds with it over the years and love to hunt with it. Despite all the fancies, it’ s still a flintlock and suffers the same problems, though perhaps to a lesser degree as do all other flintlocks. The time between trigger pull and shot still varies. Believe me; if you think that’ s a problem with a rifle, wait ‘til you try a flint fowler on quail or crossing pheasant. You’ll soon learn what follow through is really all about, as the art of hitting moving targets with a flint gun is to pull the trigger and keep swinging in front of the bird until the gun goes off and the bird goes down. Naturally, the shorter the lag, the quicker the shot and the easier the hit. And I’ve found that throwing the priming charge to the outside of the pan significantly improves the lag time, and makes my shooting more consistent.

|

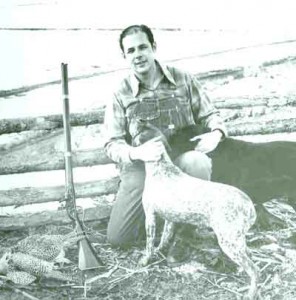

| Doc in an earlier day with copy of the Forbes doglock fowler. |

I’m reminded of two physician friends of mine that became fascinated with antique shotguns and pheasant and wanted to try out both. I was willing to help because they were willing to pay for the pheasants at the local game farm. I was possessed at that particular time of life with a fascination for English Dog Locks, and had built one. Now these are terribly ugly guns and look so antique that they are just fascinating. A fellow named John Forbes brought one over on the Mayflower. It’s still visible in a New England museum, and is much pictured as an example of the arms used by the early American colonizers. It has a flared butt, a long tapered smoothbore barrel and a huge ungainly looking English dog lock on it. This lock is one of the early varieties of flintlock developed before the more modem ”’French” lock was finally universally adopted as the simplest and most utilitarian. My doctor friends just loved it. It had a painted stock purposefully well chipped and artificially banged up and a black painted barrel just like the original. They thought I was putting them on until I showed them a photo of the real thing.

We headed for Johnny’s Ringneck Ranch, where the pheasants were especially wild. My shorthair pointer did her best that day and the birds were co-operative. The bitch put up enough birds for any hunter and those dead shots hardly missed. I was flabbergasted and they were tickled pink, One of them still has his biggest bird mounted in his office and brags about his shooting every time I see him.

|

| the shooter in front with the long barreled doglock is about to down that rooster. It’s ugly, but handles like my Berretta shotgun |

They and I were the unwitting victims of several factors that none of us figured on. First off, these two were better than average shots anyway and do very well at their local duck clubs. Second, when I built that fool Forbes Fowler, in spite of it being ugly and authentic in form and feature, I built in the pull, drop and toe of my Beretta duck gun, installed a fancy touch-hole and engineered the geometry of the frizzen and cock to match the fanciest English late-style flintlock instead of the clumsier English dog lock. It didn’t occur to me until after they were killing birds right and left that I had engineered them into thinking they were great shots with any shotgun, with any ignition.

I had also lectured them on the peculiarities of the flint shotgunning, including warning them to throw the priming to the outside before they mounted the gun. Being great sportsmen, they followed instructions and pulled off the best piece of amateur flintlock shooting I have ever witnessed.

|

| A moment later, that bird was on the ground. |

One of the tricks that I showed them was how to sharpen the flint, instructing them to keep the flint sharp for every shot. This is an absolute necessity when in the field, important enough when “shooting flying” as the English used to say, but manifestly more important when facing big or potentially dangerous game.

My usual practice when just plinking around, where an occasional misfire because of a dull flint just keeps your trigger finger honest, is to sharpen the flint once in a while, usually after a misfire. When I hunt, I touch up the flint before every shot, unless the press of circumstance is such that I can’t afford the time. I usually use a new flint with a freshly touched up edge after every 7-8 shots and indulge myself with a brand new flint at the beginning of each new day. Of course, I save those flints fired just a few times and use them later when just targeting, etc., where the shooting is likely to be much less important.

I sharpen a flint already in the gun with a screwdriver-looking affair with a brass blade. The brass is not only softer than steel, catching the hard flint edge better and knocking off a chip easier, but it also will not accidentally drop a spark into the pan. Some just tap the brass tool against the flint edge, displacing enough small chips to sharpen the edge. I like to select my chips more accurately, and deliberately press the tool against the upper edge of the flint, carefully splitting off selected chips where they will do the most good. This not only restores the edge, making it sharp and capable of showering big sparks into the pan but it also saves the flint, which you might otherwise throw away, saving bucks for other things. I can usually get 40-50 strikes from a flint granted that it remains in one piece.

I sharpen a new flint in the gun in the same manner, or hold the loose flint against the heel of my left hand with the third fourth and fifth fingers while I use the brass tipped tool in the right hand to chip away at the edge. This is the same technique used to make arrowheads, and demonstrates why the Indian warrior didn’t depend on imported flints for his flintlock.

If the muzzleloading hunter will bother to install a super quality lock in his rifle, (the lock should cost about the same as the barrel), then be willing to keep his flint knapped and sharp for the first shot of a series, than he can hunt with the same confidence as does the modern hunter.

It reminds me of a time when I was hunting close to. home in Roosevelt. I was in the Cedarview area, only 5-6 miles from my home. I had only one day to hunt and stayed close. A friend had a big hayfield there and the deer just loved the taste of his Timothy. There were a lot of cedars around his fields in which the deer bedded during the day, after eating their fill of hay.

I had to make rounds at the hospital that morning and didn’t get hunting until after. the sun was well up. By then the deer were in the cedars. My technique was to sneak through the trees, searching every nook and cranny with eye, ear and hunters’ sixth sense, hoping for a fleeting glance at a buck, hopefully with enough time for a quick shot.

After drifting through the trees for a good two hours, I finally got my wish. A nice timothy-fat four point jumped out in front of me and swivelled away through the trees. I was ready for the shot, but not the direction he took at the last instant and missed. Normally, that’s no big deal, as a miss with a muzzle gun is not too frightening. I suppose this is so because the subsonic bullet makes a “swish” as it goes by instead of the sharp ear-rending “crack” of the modern hypersonic bullet. I knew the deer wouldn’t go far, and determined to track him down.

|

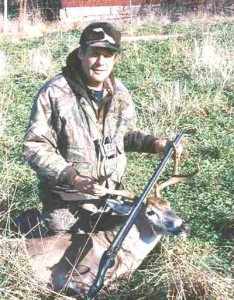

| Doc with a 7 point Missouri whitetail that fell to his 54 caliber flintlock. |

I reloaded, giving him time to settle down, but discovered that my flint was broken. Worse, a careful search of shooting pouch and pocket failed to find another flint. Home wasn’t so very far away but I hated the thought of driving all the way home just for a flint. Luckily enough, my friend had told me about some old Indian fire mounds in which he had found a few arrowheads and a corn grinder in years past. They were not too far away, less than an hours search found them, and a short dig brought forth a treasure of flint shards. I returned to the hunt with pockets bulging, tracked down that four point, and missed again, then a third time, whereupon I gave up in disgust and went home.

I wasn’t near as disgusted at missing that four point three times m a row as I was at failing to set the rear trigger and muffing the shot on the buck that Cloyd Davis had bowled over. Thinking back on it, I realize that the amount of time involved in my futile trigger pulling wasn’t long, but at the time it seemed like forever. Trouble was that I was used to the tender touch that it usually takes to fire the front trigger once the rear trigger is set, so wasn’t pulling very hard. Actually if I had pulled hard and long enough, the rifle would eventually have fired, as the DST was of the “double lever” variety, that will fire set or unset. The “unset” trigger pull is long and creepy, however, and isn’t to be recommended unless you just have to.

The truth is that I don’t like DST’s on hunting rifles. They’re just too delicate and require too much thought to manage correctly every time. I saw an expert shot muff a good chance on a buffalo once when he touched the delicate front trigger a moment too soon. He shot that buffalo right in the T-bone steak and it ran a few country miles before another few shots brought it down. Even I was on the receiving end of a DST slip up once, when I was walking up a wounded buck. I was carrying my rifle in the cross-chest position, back trigger set, waiting for the buck to bolt. I knew he was in some junipers just to my front and I was more than a little exited. My trigger finger was so itchy that when the buck finally jumped, I twitched just enough to fire the rifle in the air, driving the butt of the gun into a very delicate part of my anatomy. I’ve pretty well stuck with single triggers for hunting ever since, but do enjoy a DST at a target match.

I surely didn’t enjoy that DST when I failed to set the rear trigger, but the rifle wouldn’t have been right without one. This particular rifle was a copy of an original J and S Hawken, fullstock, brass-mounted rifle once owned by Bill Fuller of Coopers Landing, Alaska, and now encased in the Winchester Museum in Cody, Wyoming. I believe that the real thing was originally flintlock and I made my copy of it that way. The rifle was equipped with an L and R flintlock, the before-mentioned DST and a swamped Green River 62 caliber barrel 42 inches long. My load was a 615 ball weighing about 340 grains over 200 gr. FFg black powder. The patching was sperm oil soaked canvas. The rifle weighed just a trifle over ten pounds.

|

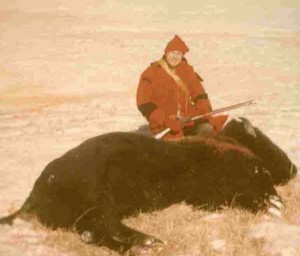

| Terry Scholes showing off his big mule deer while the rest of us look on, Pigeon Water, NE Utah, 1974. Everyone shot round ball then, with no lack of success. |

That weight was a decided asset now as I quickly set the rear trigger of the DST, cussing under my breath as the buck got further and further away. I was still down on my left knee, swinging the rifle from right to left, trying to steady its wobble as I swung into the running buck from behind. I knew that I would only have one chance, as the buck was now 150 yards away and would clear a little hill and disappear from sight in another 25 yards of running. Suddenly the front sight was past the buck with about a body’s worth of space between sight and buck. I didn’t feel my finger pull the trigger but the rifle roared, the lock time so quick there was no perceptible lag between trigger pull, hammer fall and shot. The buck disappeared in a huge cloud of white smoke, through which Cloyd appeared at a dead run. He was whooping like a wild Indian, losing his hat as he leaped up the slope, clearing sagebrush and rocks in exited bounds. I could see the buck now, struggling with a broken back, Cloyd circling to avoid ending up downhill of the pain-crazed animal. His 50 caliber percussion thumped, and the buck struggled no more.

And so it goes when hunting with a flintlock. The system isn’t a particularly easy one to manage or master, but it is intensely rewarding when it works well, that is, when you make it work well. It doesn’t mean that you will take more game than with a percussion or a cartridge weapon, nor does it mean that your hunting need be fraught with failure or frustration. It does mean that your hunting experience can be intensified and made much more enjoyable by utilizing this antique and fascinating system.

Good Hunting

DOC

150 plus Mo. whitetail with Doc and flintlock rifle