DOC’S EMPHASIS-

It must be obvious by now that Doc has changed his emphasis from the White Systems- WhiteRifles line of his in-line muzzleloaders to custom traditional percussion and flintlock guns, which is where he started 60 years ago. The White companies have been financial failures for the most part, with great inventions, terrific developement, and innovative products with superb functional elegance, ergonomics and quality. But the management could never rise to the quality of the product. In the end, teaching a new doctrine was just too expensive. The current company, WhiteRifles, is a small remnant of what went before. Parts and bullets are still available, but there hasn’t been a new design, let alone a new rifle, produced since 2005.

If you want to see what Doc does best, at present, look under ‘custom traditional‘ found top of page. If you want top see what Doc used to do, look up the old White Systems, also listed top of page: G-Series rifles: the Whitetail, M97. The GS-series-the Lightning, The BG shotgun-the Tominator, The S-series: the Super-91, Super-91-ll, M98 and Thunderbolt.

KNOCK DOWN POWER and whitetail deer

Here I am with a White Super Safari in 504 caliber, shooting a 600 grain Super-Slug over 120 grains Pyrodex-P. Range was 170 yards, shot was taken offhand. The bullet ranged from high on the right rear ribs, forward and down through the huge vessels of the heart and lungs for an instant kill. The bullet expanded to about dollar size, traveled through nearly three feet of moose before coming to rest in the muscles between two ribs far forward on the bull’s chest. The bull fell with the impact of the bullet and never wiggled. This is a good example of how effective a bigger bullet can be. Below are the ballistic reasons why bigger bullets are so effective.

Here I am with a White Super Safari in 504 caliber, shooting a 600 grain Super-Slug over 120 grains Pyrodex-P. Range was 170 yards, shot was taken offhand. The bullet ranged from high on the right rear ribs, forward and down through the huge vessels of the heart and lungs for an instant kill. The bullet expanded to about dollar size, traveled through nearly three feet of moose before coming to rest in the muscles between two ribs far forward on the bull’s chest. The bull fell with the impact of the bullet and never wiggled. This is a good example of how effective a bigger bullet can be. Below are the ballistic reasons why bigger bullets are so effective.

Ever wondered why bigger bullets slam your game to the ground like they do? Ever wondered why the game shot with short lightweight pistol bullets run a good ways before they finally keel over? I’ve not only been hunting myself for the last 60 years, but have watched as hundreds of game animals have been shot by other hunters. Almost always, they were shooting one of the popular 45 caliber, 250 grain pistol bullets in a 50 caliber sabot. Few animals were slammed to the ground. Most jumped with the hit, then ran off, only to fall later, many times a lot later. Many were not recovered. Let’s examine the reasons why.

For this experiment, I prepared three rifles with three different loads. The first, illustrated as Trace 1 below, in red, is a 50 caliber rifle loaded with a Hornaday .452 XTP hollow point bullet weighing 250 grains, Ballistic Coefficient (BC) 0.140 and three Pyrodex pellets, that’s 150 grains black powder equivalent.

The second, illustrated as trace 2 below, in green, is a .451 caliber rifle loaded with a White brand 45/40-350 PowerStar, that’s a 40 caliber hollow point bullet weighing 350 grains in a 45 caliber sabot, BC 0.300, fired with 110 grains of Pyrodex P.

The third, illustrated below as Trace 3, in blue, is a 50 caliber rifle loaded with a White 460 grain PowerPunch slip-fit bullet, BC 0.26 and a modest load of just 100 grains of 777.

We are going to study VELOCITY, ENERGY, DROP, PATH and MOMENTUM of the bullets as they relate to knock down and killing power.

VELOCITY- In this modern world, velocity seems to be awfully important. Didn’t Roy Weatherby prove that back in the 50’s? So let’s look at it first. Goodness, the Hornaday 250 grainer in trace one (in red) starts out at a terrific 2005 FPS,almost as fast as a 30-30 Winchester. The 350 grain 40 caliber bullet (in green) in the .451 rifle only gets 1550 at the muzzle and the heavy 50 caliber 460 grain PowerPunch bullet (in blue) starts out at a lowly 1450 FPS. Looks like the Hornaday would be the winner, except that it rapidly loses velocity, meeting the other two in the1200 FPS range way out at roughly 175 yards.

Randy Smith, 2004, South African mountains with nice Gemsboc and White 504 caliber SuperSafari rifle, shooting 120 g.r Pyrodex P under a saboted White 50/45-435 PowerPunch bullet, BC 0.290. 140 yards, the Gemsboc down with the shot, the bullet breaking down the front shoulder, catching both lungs and top of heart, a perfect example of a well placed bullet taking out multiple vital organs in a large, elk sized, tough animal..

Randy Smith, 2004, South African mountains with nice Gemsboc and White 504 caliber SuperSafari rifle, shooting 120 g.r Pyrodex P under a saboted White 50/45-435 PowerPunch bullet, BC 0.290. 140 yards, the Gemsboc down with the shot, the bullet breaking down the front shoulder, catching both lungs and top of heart, a perfect example of a well placed bullet taking out multiple vital organs in a large, elk sized, tough animal..

ENERGY: Most of us know that a light bullet that loses velocity rapidly will lose energy even faster. Let’s see how the same loads as above perform with energy.

ENERGY- Obviously, all the loads start out with nearly or somewhat more than 2000 ft lbs at the muzzle. The Hornaday 250 grain bullet starts out with 2221 ft. lbs., the 40 caliber 350 grain PowerStar shows 1868 ft. lbs. and the 50 caliber 460 grain PowerPunch demonstrates 2148 ft.lbs. However, within 60 yards, the lighter 250 grain bullet has fallen below both the others and is substantially lower at 100 yards. At 200 yards, it has only 734 ft.lbs. left, a relative disaster when compared to the other two, both of which have better than 1100 ft. lbs. of energy remaining.

QUESTION: But doesn’t the higher velocity of the 250 grain bullet in trace one give the hunter a real advantage? Shouldn’t the holdover be far less and the shot far easier to make with the higher velocity bullet. No? But, isn’t it this factor that we see advertised by most muzzleloading companies in their new “high velocity” rifles, loading three Pyrodex Pellets and a light , short Pistol bullet.? Let’s compare the three bullets and loads in the chart below to see just how good, or bad the total bullet drop is, relatively speaking.

DROP: The short Hornaday has the advantage all the way out. It falls only 5.28 inches at 100 yards while the other two drop 7.93 and 9.18 inches at 100 yards. At 200 yards, the difference is even more pronounced, with the 250 grain bullet falling about 26.32 inches and the heavy 50/460 falling about 40.72 inches. But hey, this is pure fall, with no adjustment for point of aim. Let’s adjust the rifles now so that they are all sighted in at 150 yards.

The rifles are now sighted in at 150 yards. The chart below will show us just how much hold under or over we will need at any specific range.

Bob Johnson 1992 with a 240 class mule deer from Utah’s Pahnsagaunt, 200 yard shot with a .451 caliber White Super-91 using 90 gr Pyrodex P and a 460 grain slip-fit .450 PowerPunch bullet, BC 0.330.

Bob Johnson 1992 with a 240 class mule deer from Utah’s Pahnsagaunt, 200 yard shot with a .451 caliber White Super-91 using 90 gr Pyrodex P and a 460 grain slip-fit .450 PowerPunch bullet, BC 0.330.

PATH: Looks like there is a whole 2 inches difference in apogee between the fastest load and the slowest, the 250 grain Hornaday shooting 3.05 inches high at 75 and 100 yards, while the 50/460 PowerPunch shoots 5.1 inches high at the same range, with the .451 in between. At 200 yards, the shooter would have to hold 8.17 inches over point of aim with the 250 grain equipped rifle while the holdover with the 50 caliber, 460 grain bullet would be 11.21 inches and the 45/40-350 in between at 9.42 inches. That’s not enough of a difference for the average eye to even see with open sights at 200 yards and would make the difference between holding low on the spine or high on the spine for a heart shot on a small Texas Whitetail if you had a good scope and a steady rest. If no rest, a good breeze, open sights or you are a lousy shot like most of us, it makes little difference.

MOMENTUM: It becomes obvious from the chart below that the heavier bullets have a decided advantage in energy, which roughly equates to killing power, at extended range,(although not within 50-60 yards), while the lighter 250 grain bullet has a miniscule advantage in holdover out to 200 yards. Holdover has little to do with killing power although lesser holdover makes the target easier to hit.

The big factor in knock down or killing power is not just energy, but is a combination of bullet weight, bullet diameter and velocity. The old Taylor Knock Out (TKO) formula (Bullet weight in lbs. times diameter in inches times velocity in ft. secs. divided by gravity in ft. secs.) yields a constant which compares the effectiveness of various bullets. The Momentum chart above approximates the TKO formula (although not the absolute numbers).

Obviously the 250 grain pistol bullet comes out a poor third. This is briefly explained by the poor 0.140 Ballistic Coefficient of the bullet, while the PowerStar 40 caliber 350 grain bullet has a BC of 0.30 and the PowerPunch 50/460 a BC of 0.26.

Jeff Winn, Canada, 1991 with record book Stone Sheep, #1 muzzleloader that year, with White Super-91, 451 caliber using 75 grains Pyrodex-P aand a .450 caliber slip-fit 490 grain PowerPunch bullet, a neck shot at 175 yards. He claims he took the neck shot on purpose. Such confidance!

The lightweight Hornaday 45 caliber 250 grain bullet scores a relative number of about 40 on the above Momentum chart, while the 45/40-350 PowerStar scores about 60 and the ‘slow, lumbering’ 50/460 PowerPunch comes out with a number close to 72 at 200 yards. In other words, the 250 grain bullet is only 55% as effective as the big PowerPunch and 66% as effective as the PowerStar at 200 yards. Even at 50 yards, there is a substantial difference.

Well, the reasons the heavier bullets are slammers while critters run off with light, short, poor BC hollow point pistol bullets should be obvious from the study above. Not only do those light bullets lack the energy to penetrate. but they also over-expand because of the wide hollow point which makes penetration even worse. Let’s remember that the bullet’s job is to destroy not just one, but multiple organ systems in its way through a game animals body. You want to plant a bullet of adequate velocity and weight at just the right angle to virtually guarantee a sudden plunge in blood pressure and flow, so that vital brain and body functions cease virtually immediately. That’s what knock down power does for you. It puts the animal on the ground where it can’t run off or run at you. A wounded whitetail might give you a second chance, a wounded cape buffalo surely will, not that you will like it.

So what would I use for whitetail? I most surely would not use a short, low BC hollow point 250 gr. pistol bullet in a sabot. If I am forced to use such a bullet, I would want it to weigh at least 300 grains, simply because those heavier bullets are made for higher magnum pistol velocities and they penetrate better in big game.. A 300+grain pointed bullet is even better because the BC will be higher. I would use the powder charge that gives me not the highest velocity, but the best accuracy, simply because it won’t matter what the BC, or the Energy, or Velocity or Drop or Momentum is if you can’t get the bullet into the boiler room.

There are a number of 300+ grain bullets available. The Hornaday 45 caliber 300 grain in a sabot is a good one except for the blunt nose. The Harvester 45 caliber 300 grain spire point is excellent with an enhanced BC , especially with their ribbed sabot. There are others as well. Federal has just come out with a 350 grain non-saboted bullet in 50 caliber. Even heavier all lead and copper coated bullets with plastic skirts are common. Experiment with them in your rifle until you get the combo you like. Nothing works better than lots of shooting to refine your loads.

What do I use personally on whitetail? A White brand ThunderBolt in .451 caliber with a saboted White 45/40-350 SuperStar bullet (45 cal. Sabot, 40 cal. Bullet weighing 350 grains) over 70 grains 209 blackhorn powder with a 5 grain black powder igniter. Muzzle velocity 1700 FPS, sight in at 140 yards, 200 yard holdover 6-7 inches, 200 yards group 3-4 inches. Above: 2015 whitetail kill 180 yards, heart shot, deer traveled 6 feet.

What do I use personally on whitetail? A White brand ThunderBolt in .451 caliber with a saboted White 45/40-350 SuperStar bullet (45 cal. Sabot, 40 cal. Bullet weighing 350 grains) over 70 grains 209 blackhorn powder with a 5 grain black powder igniter. Muzzle velocity 1700 FPS, sight in at 140 yards, 200 yard holdover 6-7 inches, 200 yards group 3-4 inches. Above: 2015 whitetail kill 180 yards, heart shot, deer traveled 6 feet.

Good Hunting

DOC

SO YOU WANT A LONG RANGE MUZZLELOADING SPORTING RIFLE-

BUT: You haven’t got the bucks to buy one outright, at least not one of the elegant custom sporting rifles that you see on this website with Doc’s signature on them, or any other well known builder for that matter.

You don’t want an in-line, you want a traditional rifle that might pass muster at a rendezvous if it had to but what you really want is a rifle that will shoot accurately and powerfully at 200+ yards and take down that big whitetail buck you’ve been dreaming about.

How about a simpler, less expensive rifle, like the one above, that shoots every bit as good as the costly ones. Still sports quality parts, just fewer of them.

THE ANSWER: to this dilemma is to build one yourself. You have to remember that the elegant reproduction sporting rifles that sell for big bucks nowadays are copies of elegant sporting rifles that sold for big bucks back in the old days, too. There were lots of equally well performing rifles that cost a lot less money back then, too, so building a less expensive one is still traditional and , best of all, just as effective as the fancy ones. They even look somewhat alike, except for a few details.

THE DETAILS: You will need a barrel, lock, stock, drum and nipple, trigger , trigger guard and buttplate, pipes for a ramrod and the ramrod. A set of sights will help, too, plus a few screws and bolts and 1/8th inch welding rod to hold it together.

You will also need a few basic tools, or access to them. A buddy with a shop and tools, a local gunsmith willing to provide drilled and tapped holes and sight slots, even taking a hobby class where the tools are available at your local high school or college.

Here is a list of the parts you will buy, the total bill should come out somewhere around $500. All parts mentioned are excellent quality. We want less expensive, but we want quality, too. Don’t scrimp on the quality of the parts, just on the number of them.

Barrel; the best caliber is .451 with grooves .035 deep and a 1-18 to 22 twist. The reason is that this caliber and twist duplicate a 45-70. Such barrels are easier to find or have made because of the popularity of the 45-70. The least costly shape is round and no more than 1 1/8 inch diameter and 30 inches long, and inch in diameter is better, far easier to carry. The best source is a barrel maker who can install the simple flint breech plug, drum and nipple while he is at it. I use Howard Kelly, who has been making barrels for 50 years and is a master. He is also less costly than Douglas or other modern barrel makers- buy one of those and you have to get a smith to pare down the barrel and install the breaching at extra cost.

A few of you might yipe about the drum and nipple but I find it the best, yes I said best, breaching arrangement there is for a muzzleloader carried on an all important hunt. Reason is that you can pull the drum and nipple out with a small wrench easily if something screws up. You can’t do that with a patent breech, only screw out the nipple and hope you can fix it without having to screw off the breech, which takes a shop , a vise and the proper tools.

Stock– either start with a plank, saw out the outline then peel off the extra wood with a rasp or buy the stock pre-carved. I advise you to buy the stock pre-carved. I use Pecatonica River Long Rifle Supply but there are others. Order their English half stock shotgun stock in maple or walnut. Walnut is a little easier for beginners to handle so get their least expensive grade of walnut, or soft maple. Ask them to cut a half round barrel channel to fit the barrel you have and a ramrod hole to fit your 3/8″ ramrod.

Lock– you will want a lock with a cut for the drum and nipple ready-made. The best is a lock made by L & R. Many supply houses carry it, it is their #300. The lock has a flat spring, quality is excellent and it has a fly on the tumbler in case you opt for a double set trigger somewhere down the road.

Drum and nipple: buy a ½ inch drum with 3/8 x 24 threads and a clean out screw but without the nipple. Buy the stainless 1/4 x 28 nipple separately. You will want to drill and thread for it only after the drum is installed. Best: have your barrel maker install the drum while finishing the barrel. Track of the Wolf labels their drum: Drum-8-5-FL

ButtPad: buy an inch thick rubber buttpad at least 5 inches long. You can find one cheap on Gunbroker.com. I bought 8 of them recently for less than $8 apiece. Brass or steel buttplates are much more expensive and much harder to install. Make the job easy and less expensive with a rubber pad. Besides , the English were putting pads on Sporting rifles before our Civil war.

ButtPad: buy an inch thick rubber buttpad at least 5 inches long. You can find one cheap on Gunbroker.com. I bought 8 of them recently for less than $8 apiece. Brass or steel buttplates are much more expensive and much harder to install. Make the job easy and less expensive with a rubber pad. Besides , the English were putting pads on Sporting rifles before our Civil war.

Trigger Guard: Traditional trigger guards in brass or steel are expensive, about $30. Find a simple trigger guard that will do the job, like the trigger guard from a White Super 91. There are lots of them still available. Any other similar guard will do. I you want the pricey one, order T/W’s TG-Express-1 in iron, it’s a bit less expensive than brass.

Trigger Guard: Traditional trigger guards in brass or steel are expensive, about $30. Find a simple trigger guard that will do the job, like the trigger guard from a White Super 91. There are lots of them still available. Any other similar guard will do. I you want the pricey one, order T/W’s TG-Express-1 in iron, it’s a bit less expensive than brass.

Under-rib: the under-rib carries the pipes that fit the ramrod. They also separate the romrod from the barrel a sufficient distance to fit keeper and key under the barrel. T/W calls theirs Rib-TR-16-20.

Pipes; You will need two. They are easily made from 3/8th inch tubing, but since you will have to buy a full length of tube it’s just as cheap to buy two simple pipes. You going to solder them to the rib. T/W calls theirs RP-RH-RH-6-I. All muzzleloading supply houses carry these simple pipes.

Pipes; You will need two. They are easily made from 3/8th inch tubing, but since you will have to buy a full length of tube it’s just as cheap to buy two simple pipes. You going to solder them to the rib. T/W calls theirs RP-RH-RH-6-I. All muzzleloading supply houses carry these simple pipes.

Ramrod: Buy a 3/8″ ramrod with brass tip installed. Everybody carries them. Used to be they were all hickory. Now there are even better woods. If you want , get a Delron rod, but you will spend three times the money. I don’t recommend them, they are too wobbly for a long barrel.

Trigger: The simplest trigger is pinned through the wood of the stock, without a trigger plate. A trigger with a plate doubles your cost. You can always go for a more elegant trigger, even a double set trigger, later one. I would start with the simple one, substitute the fancy one later if wanted. Many styles are available. The best for this application is the ‘Gibbs’. T/W’s label is TR-Gibbs-T.

Trigger: The simplest trigger is pinned through the wood of the stock, without a trigger plate. A trigger with a plate doubles your cost. You can always go for a more elegant trigger, even a double set trigger, later one. I would start with the simple one, substitute the fancy one later if wanted. Many styles are available. The best for this application is the ‘Gibbs’. T/W’s label is TR-Gibbs-T.

Sights: Here is where spending a little more is worth it. You can’t shoot any better than the sights will show you the target. I would opt for an adjustable rear and a hooded front. T/W’s best adjustable is their RS-PM-1, the best front is Lyman’s lowest hooded front with inserts, T/W calls it FS-17-AHB. Both will need dovetails cut into the barrel.

Sights: Here is where spending a little more is worth it. You can’t shoot any better than the sights will show you the target. I would opt for an adjustable rear and a hooded front. T/W’s best adjustable is their RS-PM-1, the best front is Lyman’s lowest hooded front with inserts, T/W calls it FS-17-AHB. Both will need dovetails cut into the barrel.

Finish– get a small bottle of pine oil. Linspeed is also useful as is LMF’s gunstock varnish, if you are going to finish traditionally. You will also need a small bottle of Birch-wood Casey’s Brown. Of course, you can always just paint the whole thing black with grey-black auto primer underneath.

LET’S BUILD IT

Start by inletting the barrel and tang

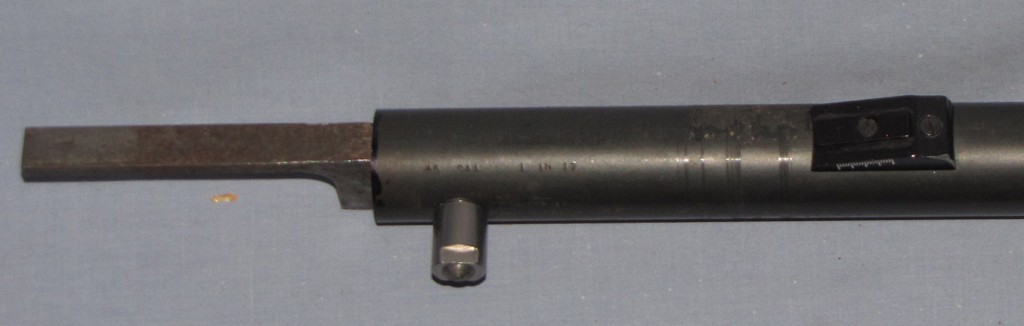

The barrel should have the tang and drum drilled, tapped and screwed into place.

Here you see the tang and drum screwed into place. Be sure they are square to each other and that the sights line up with the tang. The tang will be rounded and bent to fit the stock during inletting.

Here you see the tang and drum screwed into place. Be sure they are square to each other and that the sights line up with the tang. The tang will be rounded and bent to fit the stock during inletting.

The stock should have the barrel channel inletted, at least close. Finish inletting the barrel, including squaring up the corners of the recoil shoulder at the breech. This is done easiest by turning the barrel around and using the muzzle to make sure everything is square.. Use inletting black and a SHARP chisel.

The barrel and tang have been inletted, the tang cut to length and rounded bent to fit the countour of the stock. You can see traces of inletting black in the inlets.

The barrel and tang have been inletted, the tang cut to length and rounded bent to fit the countour of the stock. You can see traces of inletting black in the inlets.

Once the breech is inletted squarely, inlet the tang. Again, use the inletting black. You can do the preliminary inletting with a Dremel tool, then use that sharp chisel to finish the sharp corners.

Finally, file down the tang to match the contour of the wood. Drill a hole in the tang 5/8th of the length of the tang back from the barrel, centered in the tang for the 1″ x #12 screw that holds the tang in place. Countersink the screw hole to fit the head of the screw. Drill a .125″ hole in the wood and screw in the screw. Grease it lightly before you screw it in.

Inlet the drum

You had removed the drum before inletting the barrel. Now screw it back into place and inlet it into the stock. A Dremel tool with 1/4″ bit works fine here.

Barrel, tang, drum inletted. No tang screw yet.

Barrel, tang, drum inletted. No tang screw yet.

Fasten the barrel to the stock

Now remove the screw and remove the barrel from the stock. You are going to make a pin keeper from 1/8th inch steel copper coated welding rod. This is the part on the underside of the barrel that accepts the pin that hold the barrel to the stock. This is easily done by bending and hammering the rod around the jaws of your vise grip pliers. You should end up with a ‘U’ with squarish coiners. The legs should be 1/4″ long on the inside of the ‘U’. Mark the underside of the barrel 5/8th of the way from the front of the lock mortice to the end of the forearm. Make sure the marks are in the middle of the underside of the barrel. Now mark the barrel to accept the “u” you made, so you can drill a 1/8th X 1/8th holes to accept the legs of the loop. Peen the ‘U’-shaped keeper into the holes, then remove it. Apply soldering paste, then replace the loop in the holes and solder permanently into place with Force 44 silver bearing soft solder, (25,000 lb. tensile strength). Allow to cool while you are inletting the stock for the loop you just soldered.

The loops are peened and soldered into place

The loops are peened and soldered into place

Now drill a 1/8th” hole from side to side in the forestock, centering the keeper in the barrel. This is best done by measuring and marking the position of the middle of the keeper on the stock, then using a caliper to measure the distance from the top of the barrel channel to the bottom of the channel, then marking that distance on both sides of the stock.

The slot for loop with pin in place.

The slot for loop with pin in place.

Now drill from one side to the other- place your finger tip where you want the drill to come out then try to hit the middle of the finger tip with the drill. Practice this technique on scrap wood several times before you make the real attempt. Now cut a piece of the 1/8″ welding rod , trim up the ends and drive through the hole you just drilled with barrel in place.

If you want a double pin set up, then make two of the loops , drill and solder as instructed but place the two pins equidistant, measuring from the front of the lock panel to the tip of the forend.

Then inlet the lock

First take the lock apart. You will start inletting with the lockplate. Put it into place with the cutout for drum in place surrounding the drum. Mark with a pencil, then remove the wood. I do this with a dremel tool but others use a sharp chisel, The cutout should be the depth of the lockplate, or deeper, deep enough that the thicker bolster on the lockplate fits up against the barrel.

Once the lock cutout is roughly done, smear inletting black around the edges of the plate, replace it in position and lightly tap with a wood or rubber mallet or the wood butt of a hammer. Then remove the blackened wood. Repeat this maneuver until the lock plate s fits precisely.

Wood had been removed so that all parts fit and function.

Wood had been removed so that all parts fit and function.

Now screw the tumbler and bridle onto the lockplate. Mark the wood and remove the wood with Dremel tool or chisel. Mark the piece with inletting black , attempt to put the plate with parts into place then remove the blackened wood.

The lock is completely inletted with hammer correctly positioned.

The lock is completely inletted with hammer correctly positioned.

Continue until inletted with the tumbler moving freely within the inlet. Now do the same with the sear spring, sear, and mainspring, in that order. All parts should move freely in their inlets once done.

The lock is inletted, it fits and it functions. The photo shows the easy way to mark the drum for the nipple.

The lock is inletted, it fits and it functions. The photo shows the easy way to mark the drum for the nipple.

Now replace the hammer, use the nipple to measure where the nipple hits the drum, then mark. Drill and tap the drum for the 1/4 X 28 nipple. Screw in the nipple and make sure everything fits and that the hammer hits the nipple squarely.

The bolt can be left as is, it works fine that way. Fancier rifles would have a decorative escutcheon under it.

The bolt can be left as is, it works fine that way. Fancier rifles would have a decorative escutcheon under it.

The last step is to secure the lock in the stock with an 8 X 32 bolt. Drill the plate first, placing the hole at the rear of the bolster, then drill the stock from side to side using the same drill bit, then drill for the bolt using a drill large enough for a little wiggle room, then tap the plate. Be sure to use the proper size drills, first the smaller tapping drill then the larger bolt drill. Trim the bolt to fit.

Then the trigger and trigger guard

Now measure the trigger against the location of the sear. Do this with the lock removed from its inlet. Place the trigger so that the sear hits the trigger about 2/3rds to 3/4’s back. Mark the opening in the wood needed to fit the trigger.

The trigger needs to move freely in the slot.

The trigger needs to move freely in the slot.

The inlet needs to be just a touch generous so the trigger moves freely in the slot. Now cut the slot. This is done easiest with a Dremel tool and 1/8th inch bit, but you can use a drill and narrow 1/8th inch chisel just like the old timers did. The slot needs to be deep enough to fit the entire trigger with the trigger and sear touching.

Once the slot is cut, replace the lock, then trim the trigger to fit both slot and sear. Now drill a 1/8th “ hole to pin the trigger in place. This hole goes in the front, upper end of the trigger, which provides the best leverage. It is best to measure for position, mark the hole, drill the hole in the wood from side to side, then place the trigger in position and mark with the drill, remove the trigger and finish drilling the trigger. Then replace the trigger and pin with a short shaft of 1/8th inch welding rod. Now try the trigger, make sure it moves freely and trips the sear without binding.

I had a left over trigger plate so decided to add it to the rifle. It adds about$8 to the cost.

I had a left over trigger plate so decided to add it to the rifle. It adds about$8 to the cost.

Now inlet the trigger guard. Center it around the trigger, make sure the trigger fits in the rear third of the guard and that it moves freely. Trim the trigger if you need to. Scribe a line around the trigger guard then remove the wood. Use inletting black to get it just right.. Once in place , mark and drill 1/8th inch holes to fit the 1″ x #10 screws you will use to hold the guard in place.

This brass trigger guard was also a leftover with no other projects in mind. It adds a substantial $30 to the cost. Iron would have been $5 cheaper and stronger to boot.

This brass trigger guard was also a leftover with no other projects in mind. It adds a substantial $30 to the cost. Iron would have been $5 cheaper and stronger to boot.

Now put on the buttpad

First you have to cut the stock to your length of pull. Most modern men can use a 14 inch pull, but adapt the length to your best comfort. Measure from the trigger back 13 inches, or whatever your pull is less one inch, then mark and cut the buttstock at right angles to the top line of the comb of the butt. Now square up the cut using a rasp or sand on a belt sander and screw on the rubber buttpad. It will be way too big.

You can see the recoil pad is oversize

You can see the recoil pad is oversize

By the way, leaving off the buttpad saves money and is perfectly traditional. One of the finest guns I ever saw had a checkered butt, no pad, no plate, no nothing except fine stock wood and good checkering. Contrasting wood butt plates were also used, like walnut on maple or vice versa.

Now the pad is firmly screwed on and sanded down to fit the wood. You will need a grinding belt for this job and you will need to do it slow and careful to avoid dinging the wood.

Now the pad is firmly screwed on and sanded down to fit the wood. You will need a grinding belt for this job and you will need to do it slow and careful to avoid dinging the wood.

Sand the rubber buttpad to fit the stock contour on a belt sander with a coarse grit belt. Be careful not to sand off any wood. Putting some masking tape on the butt stock helps you to avoid sanding gouges.

Then install the rib, sights and lugs

The first step is to solder on the pipes. Silver solder works quite well but so does silver bearing soft solder which 3-4 times as strong as ordinary soft solder. Position the two pipes equidistant from the forend to the muzzle. Make sure you have trimmed the forestock to the length you want.

The under-rib is fastened with three 6 X 40 screws. The pipes have been silver soldered, using the lowest temperature silver solder I could find.

This distance is usually about 3/8’s of the distance between the tang and the muzzle, maybe as much as 3/8’s and a half- IE- 7/16″. The rib should butt up against the wood of the forend tightly and extend to within about 1/4″ of the muzzle. You can either soft solder it on or fasten it with 3-4 screws. The soft solder is more traditional, the screws more modern. Both work, both are about the same amount of fuss. If you use solder , use the silver bearing solder I mentioned, it’s stronger. Also, be sure to hold your pipes in place if they have been silver soft soldered as the heat will melt their solder, too. This is not a problem if the pipes have been silver soldered as the silver solder has a far higher melting temp. than the silver bearing soft solder.

You can see some dross in front of the pipe from the silver soldering job. You can also see the screw. The end of the rib is a touch shorter than the barrel, to fit a cleaning jag on the ramrod. It is also rounded so it doesn’t catch or scrape the ramrod.

You can see some dross in front of the pipe from the silver soldering job. You can also see the screw. The end of the rib is a touch shorter than the barrel, to fit a cleaning jag on the ramrod. It is also rounded so it doesn’t catch or scrape the ramrod.

If you use screws , use 6 X 40 machine screws, the finer thread is stronger. Once the rib and pipes are in place, run the ramrod in. Probably it will be a bit too big. Trim and sand it down to fit and cut to length.

The best ramrod will have a brass end drilled and tapped for accessories inside with a cleaning jag on the other outside end. Use the cleaning jag as a handle to grip the ramrod when you pull it out of the pipes. Don’t reverse it to ram the bullet, that just wastes time. Pull it out, ram the bullet put it back without ever removing your grip on the jag. Makes loading much faster.

Now shoot it

By this time, you should know what sights you want. Put them on with screws or in dovetails as indicated. Be sure you get them exactly in the center (the very top) of the barrel. Canted sights not only don’t look good but they don’t shoot where you want them to either.

The rear sight on this rifle is an adjustable by Marbles. It screws on. The front is a ramp with insert by the same Co., also screwed on. They were used because the barrel was already tapped and drilled for them.

Now take the rifle to the range and shoot it. You will want to discover if the gun functions as designed and how well it functions and shoots. You may want to adjust sear and/or trigger, and most surely the sights. Sight it in, at least close. Fire lap it if you want or need. When finally adjusted, you should be able to plant three bullets into 2 inches at 100 yards and into 4-5″ at 200, or better. I have seen many 2″ 200 yard groups. Once you are satisfied with your trial, clean the gun and get ready to finish it. See my article on accurizing the muzzleloading rifle, in Doc’s Books, under The White Muzzleloading System.

Then finish it

Polish the barrel on a wheel or use progressively smaller grits of Emory cloth to at least a 320 grit finish, then brown. I use a propane torch, heat the metal until the solution slightly sizzles on it, then repeat the treatment 6-8 times, cleaning the residues off with water and a slightly abrasive fluff between coats. Once you have rasped then fine filed the stock to shape, sand with progressively finer grits from 80 to 400 until smooth and slick. Apply stain if wanted. Alcohol based stains are easiest. Then soak with several coats of pine oil and let dry. You can follow with a gunstock varnish or not. Or just spray it with a grey auto primer then a final coat of black or other auto finish. If you want a pebbled finish, use auto undercoat. Spray it from a distance, use several thin coats.

The rifle is assembled and ready to shoot (and to hunt with, if you choose). All that’s left is the finish. That can be as simple as a can of spray paint. Auto finishes are best, with a primer under coat.

and go hunting

The is the best part. What you have constructed will kill a whitetail at 200 yards with ease, as long as you can hold the gun and see the sights and target at the same time. Last year I used a similar rifle in .451 caliber with a saboted 350 grain bullet over 70 grains of 209 Blackhorn powder with a 5 grain black powder igniter to pop a big whitetail at 180 yards. Targeting this 1700 FPS load had shown that sighting in 3″ high at 200 yards put the bullet 6-7″ low at 200 with three inch 200 yard groups. The buck was fighting with a smaller buck, stepped back for a moment just at dusk. The bullet took the big aorta off the top of the heart. He didn’t go 6 feet, whirled around and went down. You can do it, too!

Good Hunting

DOC

PS- This adventure isn’t over. I am building another one of these. I will post photos and description as it grows up. DOC

BLACK MAG POWDER

Back in 1994, I ran into Tony Chiofffe at the SHOT show. He was promoting his new Black Mag replacement powder , an ascorbic acid based powder that looked for all the world like a handful of sand. I shot some and fell in love with the stuff. In 1995 I killed 12 head of big game with it, all deer size or larger and including a huge moose at 170 and a big caribou at 250 yards. Unfortunately, Tony’s health was bad and he died before the product could be fully developed in the market. Black Mag disappeared for a few years but has finally resurrected. I have been shooting it again lately and it appears to be every bit as good as it was originally.

The powder is sandy looking, not black like we all expect, about FFFg size and pours freely out of a measure. I was shooting 80 grains of PyrodexP and fffG 777 a few weeks ago, with a 504 caliber M97 Ultra Mag equipped with 26 inch barrel, loading it

under a 460 grain Power Punch bullet. This rifle is particularly accurate with its Leopold 3 X 9 scope. I was shooting rocks, as the red rock cliffs around here offer a great place for marking bullet placement at long range. The hits are plain to see against the red background, a lighter splash on the rock surface, which weathers and fades back to red within a year. It’s a great way

to teach yourself long range distance estimation without using a range finder. Pick an elk sized rock, estimate the range and drop of the bullet, pick a heart sized target on the rock, then try to hit it. I was shooting up to 400 yards

with most shots at 200-250 yards. It was pure fun.

I could tell very little difference between the three powders, shooting them interchangeably. One seemed to be as good as the other. All shot into the same group as the others. It was as easy to hit an elk’s heart at 200 yards with one as with the other. The 777 seemed a touch more potent than the PyrodexP and the Black Mag a touch more potent than the 777, judging from the recoil (I left the chronograph home) but the practical results at the distances I was shooting were effectively the same. I did not clean the rifle the entire afternoon until the shooting was over. Neither did I pick the #11 nipple or shift the breechplug

during the shooting session. The bullets loaded easily, one finger on the ramrod with all the powders, but the Black Mag would clean out the harder residues from the other two with a shot or two. Where usually a hard crud ring develops with long shooting strings using Pyrodex and 777, the crud ring was blown away with the Black Mag.

The real difference was in the cleaning. I purposefully shot a string of shots using just the Black Mag to finish up the shooting session, wanting to know if it cleaned as easily as it originally did. I was not disappointed. I usually clean a barrel dirtied with Pyrodex or 777 with 4-5 patches wet with my blue SuperClean then follow with 4-5 dry patches, ending with an oiled patch.

The Black Mag dirtied barrel cleaned with fewer patches, taking only three SuperClean wetted ones before going to dry patches. I don’t think the Black Mag is any more soluble in water and alcohols than the others, but I do believe there was less residue, thus a little easier cleaning.

I am delighted to see Black Mag back. I have no idea what the stuff costs or how widely available it is right now, but I can testify to how well it shoots and cleans. Of all the powders I have ever used, it burns cleaner and shoots better long strings than any other as the residues are so much less. I still need to get it on the chronograph and also do some true accuracy testing, but

for general hunting: ie- taking out an elk’s heart at up to 250 yards, it’s fine stuff, easily as good as the other two.

A quick note on Pinnacle and American Pioneer powders. The folks at Goex were delighted that I was interested in Pinnacle and arranged to send some for testing in White rifles. American Pioneer was another matter. They could have cared less, insisting that all the research needed was already done. I suggested that a recommendation from me might be a powerful argument for a shooter to buy it but just got a horse laugh at that egotistic sally. I will report on Pinnacle as soon as I get some. American Pioneer will wait until the company is a bit more co-operative and not afraid of independent research.

Good Hunting

DOC

PS- i’ve been using Black Mag to accurize barrels for a while now. I am even more impressed with it. It cleans so easily! And it is very accurate with PowerPunch bullets. DOC

209 PRIMERS IN W-SERIES RIFLES

There has been considerable interest on the part of some shooters in switching the #11 cap usually found on W-series White rifles (Super91, M98 Elite Hunter, Super 91-II) to 209 shotgun primer. I have never been a great advocate of the 209, usually preferring a musket cap for my own hunting because of its speed of removal, so have been pleasantly surprised in the

last few weeks while working with a pre-production 209 kit in a new .504 caliber Super 91-II. The surprise comes from several fronts as I had not expected such good results as I got.

The first surprise was that the 209 primer stayed in the primer pocket of the White 209 Breechplugwith every shot. The second was that none were blown to pieces. I had gone to the range prepared with hat and safety glasses expecting that primers or pieceswould be flying close by with every shot. I attribute these surprises to the good design of the breechplug, which after considerable trial and error has evolved into its present form. The primer pocket holds the 209 primer firmly in place due to the double wound spring wrapped around the hex head, There is also a double pressure release hole drilled through from side to side. This allows excess gases to escape to either side rather than blowing the primer out of the pocket. Another surprise was the ease with which the 209 came out of the pocket after firing. It took a fingernail, but the first three flipped out easily, almost by themselves. (And who gets more than three shots on a hunt?) After a dozen shots, it took two fingernails but still came out easily enough for casual shooting. The lesson here is to keep that pocket clean for the first shot of a hunting day, if for nothing more than to speed up the second shot if needed.

Another surprise was the consistant accuracy of the rifle. I used two loads, 70 grains of 3fG 777 and a 460 grain PowerPunch bullet and 100 grains of Pyrodex Pellets (that’s 2 each 50 grain pellets) and the White 320 grain saboted hollow pointed Shooting Star.I used the Remington 209-4 primer made for the 410 shotshell or the CCI Trap & Skeet primer in all loads. I have found that these primers are by far the most consistent from load to load in White rifles. Unfortunately, Remington has stopped making the 209-4. Other stronger 209 primers have not been nearly as consistent.

I was not terribly surprised by the accuracy of the 70/777/460PowerPunch load as it is almost universally accurate in White rifles fired with #11 or musket caps. But I was very pleasantly surprised by the 2 Pyrodex Pellet/320 grain Power Star load. I had saved some 50 grain Pyrodex pellets since last fall, leaving the box open to the air, but in a high, dark, dry place, to promote aging. I had intended to see how badly they shot, since prior experience with aging pellets had been adverse. Lo and behold,

the load shot into 4 inches at 150 yards with open sights and my old eyes. Maybe I was just lucky but maybe Hodgden has solved the pellet aging problem.All previous experience had been with #11 or musket caps. Anyway, I was extremely pleased with the results.

I also discovered that the combination shot very much like the same load in a White Thunderbolt rifle. The large amount of flash from the 209 primer in the short White breechplug promotes faster burning of the powder, higher pressures and higher velocity. I was impressed that the same rules promulgated for the ThunderBolt apply to the 209 in a Super 91 or M98. That is, you won’t need as large a powder charge to get the same performance as with a #11 or Musket cap. You also will do better with

heavier grained powders, like Pyrodex Select and 2Fg 777 rather than PyrodexP or 3Fg 777. Pyrodex pellets also work well as long as you use a saboted bullet. Work up the load from 70 grains in 5 grain increments until you get the performance and accuracy you want. it’s rare to need more then two Pyrodex pellets with a White bullet, even for the largest elk or moose.

I was originally quite surprised at how much the 209 enhanced performance. I previously had been unpleasantly surprised at how full power 209 primers degraded accuracy. It was only after switching to Remington 209-4 primers, made for the 410 shotshell, that accuracy returned to normal levels. So never use a magnum primer, always prefer the Remington 209-4 (now replaced by the ‘Kleanbore’) if you can get any. Winchester is also now making a special 209 for muzzleloaders. If you must

use any primer other than the ones specifically made for muzzleloaders, then use the weakest one you can find, like those made for low power trap and skeet loads.

There was no surprise in the amount of blowby left in the breech after each shot.It was about the same as with any #11 or

musket cap. Since the touch-hole in all cases is the same diameter, it would be reasonable to expect a similar amount of blowby with similar loads. Cleaning this area after shooting should be no worse than with the #11 or musket cap.

The White 209 breechplug will universally fit any White rifle so far made and has the same 3/8 inch diameter industrial hex head that will fit any 3/8 inch hex wrench- no special tools needed for installation or removal. Use the 1/4 inch socket set in your tool box if you want. Grease the 209 breechplug with White’s new Super Blue moly breechplug grease when you install it, just as you would the old #11 nipple-breechplug, so it will come out easily when it’s time to clean.

I have recommended to White Rifles LLC that they immediately bring the 209 primer kit for W-series rifles into the market. There will be a new breechplug to replace the old one and a new hammer with firing pin to replace the old one for #11 or musket cap. There are no other parts changes. I don’t know what the cost will be. I have also recommended that they carry appropriate primers, which can be hard to find, thereby solving the ‘find’ part of the problem for our shooters. This involves getting a Hazmat license so it may be a while before that happens.

Good Hunting

DOC

THE NEW 336 PRIMER

|

| White short 336 Breechplug and 336 primer. The 336 Breechplug is the same size and thread as other White Breechplugs. The 336 primer is an adaption of the old S&W Short cartridge. It uses a small pistol primer and is reloadable with common reloading tools. |

It has long been apparent that the 209 shotgun primer is not the final answer

to muzzleloading ignition. Results with the common brands of 209 primers has been erratic to say the least.

For one thing, 209’s are way too fragile to stand up to the higher pressures

encountered in most muzzleloaders unless supported by a metal case, as in the Savage or a solid breech design, like the White T-Bolt. Ordinary shotgun pressures are low, in the 8-12000 psi range. Pressures in muzzleloaders can be as high as 30000 although most loads are less then 20000. Especially potent loads in slam-fire rifles can be expected to destroy the primer, with lots of leak to the rear to dirty up the action.

The weakness link in the common brand 209 is its thin copper or brass rim, which is not stout enough for sure extraction. This rim bends easily and does not support the edges of an extractor well. If the 209 gets stuck in the primer

pocket, and this can happen easily with black powder residues, the primer can be a regular bitch to pry out, simply because the rim will not stand up to prying. In consequence, most muzzleloading manufacturers have made their primer pockets excessively loose or shallow, or both, resulting in lots of blowback and a dirty breech.

209 primers are also quite sloppily made, with a lot of size variation between brands and even individual lots. This is natural, as 209’s are made to fit in the back end of soft plastic shotshells, with thin brass sheathing and often paper wadding. That means that a lot of variation in size, though not in quality of ignition, can be tolerated. Alas, this variation does not work well in steel primer pockets. Again, the solution is a larger and shallower than needed primer pocket with lots of blowback.

The one thing that 209 primers do well is ignite shotshells. They do this well because the amount of primer material is relatively large, and relatively surefire with a light firing pin strike. The one thing that shotgun shooters demand is sureness of ignition. They do not need accuracy, as they depend on a pattern of shot to harvest their game or break their clay. Thus, the amount and temperature of flame in a shotshell can be far in excess of that in a rifle or pistol cartridge. This situation has resulted in several problems in muzzleloaders, the worst of which is ‘over-ignition’, a term that describes too much flame and pressure for accuracy or safety.

Rifle shooters long ago noted that the most accurate loads were those that ignited progressively, from the back end. Pressures are lower, burning rates are more consistent, bullet jump is avoided and accuracy is enhanced with lower power primers. I well remember loading 308 Winchester target loads with special cases made for small rifle primers, just to enhance accuracy. Target primers are always loaded with less priming material than hunting loads.

Bullet jump is probably the bigger bugaboo with 209’s in muzzleloaders. The common brand 209’s are so powerful that they will throw a bullet clear out of the barrel all by themselves. There is no great velocity there, but the fact that they will is evident of their greater power. It seems that this greater power results in the muzzleloading bullet being shoved ahead by the primer

alone, before the conflagration of the powder catches up to it. The shove is naturally going to be quite variable, so the distance up the barrel before powder burn catches up is going to be variable as well. Accuracy problems are understandable.

White long ago recommended the use of the Remington 209-4 primer in its 209 using rifles. This primer was especially made for the 410 shotshell and had about half the power of the ordinary 209 primer. It enhanced accuracy in White rifles, but was hard to find at the ordinary sporting goods store. I had to ship mine in from far away and had to buy 5000 at a time to get them. Remington ceased production of the 209-4 last Spring, but has apparently substituted the ‘Kleanbore’ line of 209 primers. Other manufacturers have advertised 209’s made especially for muzzleloaders, the RWS primer being advertised for at least the last year, but I have yet to see any of them in Sporting Goods stores. Using the lowest power 209 available is the only thing a shooter can do.

With all this in mind, several years ago I started looking for an answer to the problem. It was obvious that some kind of primer containing case would probably do the job. The problem was which one. Savage turned to a solid metal case for the 209 primer in its rifle. The resemblance of their case to the back end of a 30-06 is obvious. I found that its size and weight was a deterrent to its use, although it seemed to work well, the very length cooling down the priming flash by virtue of its distance from the powder charge.

Others wrote about shortened 22 Hornet cases, using the small rifle primer. I tried this in a re-barreled Remington single shot shotgun. I cut off the barrel in front of the rotating lug, bored out the shotshell chamber on the lathe and fitted a White 504 barrel to the stub, soldering it solidly into place. The barrel was already drilled and tapped for the White nipple breechplug. I modified a White 209 breechplug, the one used in the ThunderBolt, to take a shortened 22 Hornet. I found that it ignited any powder I wanted, including smokeless, but did not contain the blowback. The shortened case wall was just too thick to expand with the shot. Besides, I had to shorten the Hornet cases, a major pain without an expensive hardened cut-off die.

I considered the 38 special case but it was too big and too long. The 38 S&W was shorter but still too large in diameter to fit the basic White breechplug. I did not want to have to change the interior diameter or legnth of the breechplug pocket, which so far has been the same in all White rifle barrels, no matter when made. The 32 mag was about the right diameter but was way too long for the breechplug and I did not want to have to cut them off. Rimless cartridges were available, but too hard to extract. I tried 25 and 32 Colt auto cases, found that they worked quite well, containing all blowback despite the short length, but their rimless cases were hard to extract from a Pyrodex contaminated pocket. I decided to stick with rimmed cases.

One day I was in a local hardware store and noticed a display of cartridges. They were at eye level or I never would have seen them Two boxes of Remington 32 S&W were displayed. What attracted me was the flatness of the box, telling me that the case was very short. I grabbed a box and popped it open. I knew that the 32 S&W (Short) was the first 32 caliber center fire cartridge ever made by S&W, originating back in the 1880’s or earlier. I thought that it had bit the dust long ago and was no longer manufactured. Lo and behold, these were indeed newly manufactured 32 S&W’s, come to find out a caliber favored by Cowboy Shooters for small pocket pistol matches and currently produced by both Remington and Winchester with 80 grain bullets at about 700 FPS.

I bought those two boxes, pulled the bullets and reamed a proper .336 pocket to fit in a White breechplug. First rifle I tried was a re-barreled H&R .410 Topper, cut off in front of the lug and with a White 504 barrel sleeved and soldered in place. Worked fine with absolutely no blowback. Extracted easily with its substantial rim. Proved to be large enough to handle quickly and easily, being somewhat larger than a 209 primer or 25 auto case. I then adapted a ThunderBolt to fit it. That took about 30 seconds, long enough to screw out the 209 beechplug and screw in one for the new primer. Once again, excellent results. No blowback, surefire ignition with all powders, thick rim made for easy extraction and size just right for quick and easy handling. Not too large to fit into the breechplug even with cold fingers under a scope, not too small to be easy to get hold of in a hurry. And the rim would adapt to a priming tool easily.

|

| Theoriginal 32 S&W cartridge is illustrated left, the White 336 Primer in themiddle, a fired 336 Primer on the right. Note that staining on the fired primerdoes not extend to the base of the case, The thin wall of the primer’s caseseals off powder gases with no leak to the rear. |

I took the concept to Africa in July 2004, using a T-Bolt .451, where it proved viable. I shot all the nine animals that I took with it, never fumbled a primer once, and used fingers alone to load the primer on the eleven shots I fired at critters, plus about 20 practice shots. Loads went as long as three days between loading and firing. eight out of nine shots were one shot kills, a Kudu taking the other three. Ignition was sure, with no misfires, and accuracy was phenomenal, my 1600 FPS load shooting into an inch at 100 yards with the 45/40-350 PowerStar saboted bullet, no cleaning between shots.

The cases are also reloadable. My CH reloading press handles primer extraction and re-priming without a hitch. For those of you who do not reload, all you need is a hand held priming tool, the proper case head holder and a common punch and something to hit it with. RCBS, Lee and CH all make hand held priming tools that cost less then $30, the Lee being the cheapest at less then $15. Case head holders cost less than $4 and some of the tools have a universal head. Punches are available at hardware stores as are small hammers. Many brands of ‘small pistol’ primers are available, all made to high standards of size and power. A magnum version of the small pistol primer is also available if you want.

If you use the new primer with Black Powder or a substitute, and want to reload it, you will want to clean out the black powder residue after shooting. This is a simple task. replicating what you do with Black Powder cartridges. I throw the spent primers in a cup, drop in a drop of detergent and add hot water, then swirl the solution and primers around for a few seconds. I do the swirl a second time with a rinse of hot water only, then dump the rinse and spread the cases out on a paper towel to dry. You can speed up the drying in an oven at low heat if wanted but it’s really not necessary. Once the cases are dry, they can be re-primed.

I once recommended that White offer the #336 primer conversions for ThunderBolt rifles and that the concept be incorporated into the new Alpha rifle once it is in production and the 336 breech-plug is standardized. One further modification is advisable. The diameter of the flash-hole in the usual White solid Breech-plug ends up at 80 thou once the plug is drilled and reamed for the 336 primer. The smaller the flash-hole, the less the blow-back and some claim the better the accuracy, but also the greater the chance of a mis-fire because of the chance of flash-hole plugging. Muzzleloading target shooters often insist on flash-holes of about 30 thou, but few targets charge and stomp you into red mud. I toyed with the idea of a replaceable flash-hole a la Savage (it;s a simple short hardened screw with 0.032″ touch-hole leading off a hex), and finally got it done here lately, installing one in the breech-plug of a modified H&R Topper. It works fine and all the powders I tried ignited without a hitch, due probably to the shortness of the White Breechplug.

32 S&W Short cases are available at many sporting goods stores and over the web. The caliber has become very popular for CowBoy Action shooting in small pocket pistols. Cost is about 10 cents apiece in quantity. Small pistol primers in both regular and magnum persuasions are available everywhere. So are the reloading tools.

By the way, one of the quick ways to get the spent case out of the primer pocket is to simply open the action after the last shot and reload the rifle. Don’t bother to remove the spent primer. The new bullet will act somewhat like a piston and usually pop the spent case out of the pocket when you shove the new bullet down the barrel. It works every time if you keep the primer pocket reasonably clean.

Good Hunting

DOC

The SCS Sabot and SCB Bullet

I believe that the biggest bugaboo for both traditional and modern-day muzzleloading is cleaning the rifle between shots. When I first joined muzzleloading back in the 1950’s, the first lesson was that the rifle had to be cleaned between shots. I found this fine on the target line, but I found it to be a real pain and impossible, if not dangerous, while hunting. I always imagined myself furiously cleaning my rifle while Old Ephraim popped his teeth at me, enraged because the first bullet didn’t quite do him in.

A serious reading of the muzzleloading literature from the bad days of the French and Indian war up through the many battles of the Old NorthWest fail to show me that any Indian fighter or serious hunter had any interest at all in cleaning his rifle between shots. The literature of the early west also confirms that no wise frontiersman cleaned between shots. Indians and grizzly bears were just too ferocious and fast.

Thus it was, as a serious modern-day muzzleloading hunter, that I found myself pondering the best way to avoid cleaning, in fact, pondering the best way to shoot as many times as I could before the gun clogged up so much that it simply had to be cleaned.

I found the answer in part in the White Muzzleloading System with its tightly fitted but slip-fit elongated bullet. The world-wide experience of the Mini-Ball, and the later British experience with Whitworth’s elongated slip-fit hexagonal bullets convinced me that we moderns could duplicate and maybe even better the performance of yesteryear. I was right, largely because of modern industrial techniques and the development of Black Powder substitute powders. Pyrodex P came along at just the right time.

However, even that superior system did not totally answer the problem. I quickly found that shooting in the dry West limited the number of shots I could fire with a White rifle and bullet before the powder residues build up enough to inhibit accuracy and retard a quick reload. I also found that shooting in the wetter East and South, though sloppy, was much less limited. Once, at a demonstration in Georgia, we fired a White rifle and bullet 219 counted shots with never a cleaning rod down the barrel while we watched our competitors clean after every shot.

Of course, that’s not hunting. A muzzleloading hunter gets one or two, at best three shots at fleeing game, with rare exceptions. Any more than that means he’s got the wrong rifle or he’s the wrong man for the task. What the hunter needs is quick reloads, for that occasional circumstance that demands a second shot, with accuracy undiminished from his first shot. Years ago, I was cleaning up some old stuff, an accumulation of antique black powder bullets (both muzzleloading and cartridge) and some old books. I idly glance through the bullets, picking up several made for black powder cartridge guns. These were paper patched. I knew that paper patches had never worked well on muzzleloading hunting rifles, the paper patch being too fragile, although they are very useful on mechanically loaded target slug guns, but they caught my attention.

Before the day was out, I had thumbed through the books, especially attracted to one on Civil War cannon by Harold Peterson. He had illustrated the slip-fit shells used on those muzzleloading monsters, showing the mechanisms that caused expansion in the bore when they were fired. All were loaded slip-fit, the slightly undersize shells sliding down the lands of their rifled bores. There were several with expanding copper bands and some with flaring copper butts. None looked like they would work in a modern day muzzleloading rifle. They were simply too complicated to manufacture or function reliably. While thinking on this, I picked up a more modern bullet with a copper gas check on it. I glanced at it and turned to throw it in the discard pile. The thought struck me like a brick to the side of the head. Why not an expanding gas check, loaded land-to-land size, expanding to groove-to-groove size with the shot? Seemed like a great idea. So simple, like all truly great inventions. But on second thought, I was sure someone had already thought this one up. I pretty nearly forgot the subject for several months, then had a slack day. I spent it researching the concept. Lo and behold, it appeared that no other inventor had ever thought of the idea, or at least patented it.

Looks like a gas check, but it’s far more then that. It not only loads easily, protects the sabot or bullet from gas cutting, evens up pressures and enhances accuracy, but also cleans the barrel with the shot. Every shot loads and shoots the same as the first shot. Clean-up is easier, too.

Intrigued, I arranged to have some made. The first ones were crude and hand stamped, but they worked!! I was pleased, not to say ecstatic. I originally tried them with ordinary loads, up to 100 grains PyroP and a White saboted 435 gr PowerStar bullet in a modified PowerStar sabot . They worked fine. The bore was uniformly clean from shot to shot and the number of patches required for eventual cleaning the rifles was fewer by half than without the Self-Cleaning Sabot. It was clear that I had a superior idea and that it worked quite well. I tried it with the dirtiest black powder I could get hold of, some heavy grained old stuff we used to use in small bore cannon. To my amazement, it even swept that filthy stuff out of the bore.

I also tried the device on the back end of my PowerPunch bullets. I had to machine each bullet on a lathe to fit the SCS device on the back end. I called it the SCB for Self Cleaning Bullet. To my vast delight, the device worked there just as well as it did on a plastic sabot. It worked every bit as well on heavy loads, like 140 grains PyrodexP and a 600 grain PowerPunch as it did on lighter target loads, keeping lead and powder residues at ‘first shot’ levels. I subsequently used the 504 caliber 600 Power Punch with SCB device over 140 grains Pyrodex P to take the new world record Asian Water Buffalo. Groups ran 1.5 inches at 100 yards for 5 shots. Interestingly, if I used the same 600 grain bullet without the SCB device, accuracy went to hell above 120 grains. In effect, the SCB device added another 20 grains of powder to power limits with excellent accuracy while affording easier loading and cleaning at the same time.

Now, one of the reasons that I advocate Pyrodex P in most White rifles is that it burns more cleanly then Black. Use Black Powder and you will have to clean between shots , even with the clearly superior White Muzzleloading System. Use Pyrodex-P and you’ll get far more shots without having to clean than with Black. Now, with the copper SCS device on my sabot, I can go back to using Black Powder if I want. I tried it with all the other powders as well, some old Arco, ClearShot, CleanShot, Pyrodex RS and Select, and every brand of Black Powder available. It worked with all of them, keeping the barrel as clean as if every shot was the first shot and making clean up chores at the end of the day much easier.

It’s obvious that the device will work every bit as well on a lead bullet as on a plastic sabot. It’s also obvious that it will work in black powder cartridge rifles too. By summer White hopes to have SCS sabots with PowerStar bullets and SCB PowerStar bullets available for purchase. They will be available in 45 and 50 caliber to begin with, other calibers later. SCB bullets and SCS Saboted bullets for all calibers and all rifles with all available rifling twists will most certainly follow.

Watch for them. They will change your muzzleloading habits dramatically. Just think, you’ll never have to clean your muzzleloading rifle after a shot in the field again. And cleaning it at home after a shooting session will be much easier. No matter what brand rifle you shoot, White or otherwise, the new White SCS will work for you. DOC

Here is a photo of the 600 grain SCB bullet used to kill that big Asian Water Buffalo with me and Randy Smith behind it, before loading and after retrieval from the buffalo. Obviously, the copper SCB gas check stays with the bullet, expanding and flattening out, preventing gas cutting of the bullet base and cleaning out powder and lead residues as it flies down the barrel.

Want to see a collection of really fine rifles? just click on the ‘custom traditional’, ‘custom modern’ or ‘Archives’ hyperlink above

AN UNUSUAL HAWKEN

As a group, most students of Hawken rifles believe that neither Jake nor Sam ever produced a flintlock rifle in their St. Louis shop. They may have, of course, but if so, none were marked or otherwise identified. The Hawken rifle illustrated below may be the exception.

One of my great blessings was the US Army, who in their wisdom, sent me to Alaska for two years back in the late 1960’s. I arrived there in Feb, 1966 and almost immediately made the aquaintance of Bill Fuller, who ran a gunsmith shop at Cooper’s Landing, on the Kenai Penninsula, about an hour and a half out of Anchorage. Bill had a half dozen original Hawken rifles at the time, including the one shown below. This particular Hawken was in excellent shape, with a heavy slightly swamped barrel in 58 caliber. The bore was likewise in great shape and it shot quite well. The stock was walnut, unusual for a Hawken, the furniture brass, also unusual for a Hawken and the styling is pure Maryland with a Lancasterish bent. If this rifle had been produced in Christofer Hawken’s Maryland shop, it would not be unusual at all. But, no, the barrel is clearly marked J S Hawken, you can see that in the lower photo. The rifle also has a typical Hawken style patent hooked britch with long tang, but does not sport the long double-set trigger bar of the more typical St. Louis Hawken rifles. The lock is clearly a conversion from flintlock. The holes for frizzen screw, frizzen spring screw and frizzen spring detent are clearly seen in their usual places on the lock plate. The barrel is 40+ inches long and the rifle weighs 14 lbs.

was likewise in great shape and it shot quite well. The stock was walnut, unusual for a Hawken, the furniture brass, also unusual for a Hawken and the styling is pure Maryland with a Lancasterish bent. If this rifle had been produced in Christofer Hawken’s Maryland shop, it would not be unusual at all. But, no, the barrel is clearly marked J S Hawken, you can see that in the lower photo. The rifle also has a typical Hawken style patent hooked britch with long tang, but does not sport the long double-set trigger bar of the more typical St. Louis Hawken rifles. The lock is clearly a conversion from flintlock. The holes for frizzen screw, frizzen spring screw and frizzen spring detent are clearly seen in their usual places on the lock plate. The barrel is 40+ inches long and the rifle weighs 14 lbs.

[/two_third_last]

Above are Bill Fuller and the Maryland/Lancaster style Hawken-St. Louis marked rifle, The photos were taken the summer of 1966. You can see the swamp in the octagon barrel. Note the typical, late Maryland style brass buttplate and the late brass patch-box. I call it late because the side plates are so plain and there is wood between the lid and the side plates. The side plates are decorated with a wobble of ‘chicken tracks’, a simple form of engraving. The trigger guard matches the style of the patch-box and is big enough to carry the double set trigger. The DST trigger bar is short, in typical early Eastern style. If I had to date the rifle by those features, I would say it was made in the East, probably Maryland, in the 1820’s.

The lock plate is also late, with the flat plate and abbreviated pointed tail of later flintlocks. It is probably a commercial lock, imported from elsewhere and sold to the gun-making trade. The frizzen and frizzen-spring screw-holes have not been filled, as was a common practice when converting locks from flint to percussion yet the finish on the lock is excellent with traces of color still present. The Hawken snail breech has filled in the flintlock pan area quite nicely. There is a bit of wood missing from just above the forward extension of the lockplate, implying that the rifle saw at least some use during its active life. The oil finish on the walnut is still in good condition, there are comparatively few wear or use marks, so was sparingly used or awfully well kept.

[one_half] [/one_half][one_half]

[/one_half][one_half] [/one_half]

[/one_half]

The side-lock plate is brass and Marylandish with a curved bottom and sparing engraving. The cheek-piece is typical of Maryland/Lancaster rifles. There is no other carved decoration anywhere, which indicates production in the late first quarter of the 1800’s. You can see the Hawken style long tang, which appears to barely fit an older short tang mortice. Look closely and the earlier mortice marks stand out about a third of the way back on the long tang. the Hawken stampings stand out in the rightward photo. Look how far forward the rear sight is, a feature often seen on Eastern rifles of all schools.

The real questions are obvious. Who made it? When was it made? Where was it made? When was it converted, if it was converted. Did the Hawken brothers make it or did they convert it later, using their Hawken breech and long tang? I am sure that every reader will have an opinion. I am going to hazard mine. You may agree with me, or not.

I very much doubt that a heavy rifle like this one was made in Maryland. By the 1820’s, Maryland rifles, in common with Eastern rifles of most schools, were tending towards small calibers. Big game had disappeared by then as had the threat of frontier war. Big and heavy indicates manufacture in the West or at least for use in the West.. It was probably made in St. Louis for the transcontinental trade.

It was probably originally flintlock, then later converted to percussion . Its excellent condition probably means that it never went across the plains and was never used in the mountains. The owner was probably local, wealthy, demanding a true Hawken conversion rather than just a common drum and nipple, which was much cheaper. The care that it has obviously had indicates a careful and sparing user with enough means to get what he wanted.

When did the Hawken’s mark it? Obviously, sometime during Jake’s and Sam’s partnership. Who knows if they built the rifle in the first place. We only know that at some time it passed through their hands and they marked it, probably because they converted it. I suspect they built it. They certainly knew the style. It was probably one of their earliest rifles, done on custom order, before they developed the classic Hawken style for which they are so famous, then later converted and marked.

DOC WHITE

PERFECT CAMO, PERFECT CALL – Turkey 2011

I wish I had a picture of this. There I was, sitting in a beach chair, surrounded by two foot high grass, with a bull elk 20 yards away. The bull was looking straight at me, nose and head thrust forward, ears at attention, eyes searching. The only question was how soon he was going to see me and alert the whole country that I was there.

This scene had all started a month earlier, in early April of 2011. I and two of my best buddies, Les Bennet and McCord Marshall, arrived in Texas on the eastern edge of the Big Bend country to hunt turkeys. It’s a trip we take annually, the best reason being that we can take 4 turkeys in this part of the world where at home we only get one.

Normally, the hunting is terrific, with plenty of birds in the strut and lots of opportunities. This year was destined to be different. Where usually the weather was pleasant if not a bit too warm for us cold country boys, now it was cold one day, down to 63, or super hot the next, up to 105. Where usually the wind was a pleasant breeze it was now a honking blast, with gusts what would knock over your carefully arranged cover and almost take you to the ground. It was tough to even keep powder in the pan of my flintlock. Where before the birds were well into the strut, running at my amateurish calls to be first to get to what they thought was a hen, the strut hadn’t even started, or maybe it was already over. Calling actually sent them running the other way.

Naturally, I brought along a brand new flintlock fowler, this time a copy of what I thought a Chief’s Grade northwest gun might look like. It had a nice cherry stock and a 12 gauge Colerain octagon to round smooth-bore barrel with one of my custom made interchangable .660 chokes. I was throwing 1 7/8 oz of shot surrounded by a White tapered shot cup ( tapered so you can get it into that tight choke) over a couple of wool Wonder Wads and 100 grains of FFg Black Powder. It was a great load, especially with the #7 nickle-plated hardened shot I used, throwing super tight patterns at 40 yards, usually good for 8-10 hits in head and spine.

The gun, meticulously made as it was, didn’t do me much good this year. The priming powder stayed in the pan as long as the frizzen was down, but as soon as to popped open with the shot, the priming went flying in the wind. No shot, no turkey. I had a big tom in my sights at 30 yards, head up, looking right at me, giving me time enough to prime, cock and pull trigger 4 times before he finally got the idea that something was amiss and left the scene. No wonder Alexander Forsyth invented the percussion system.