A BEAR FOR THE DOC

I peeked over the tundra covered hump of the hillock in front of me. I could see Pat about 40 yards downhill, standing just outside of the brush patch that we’d been watching for the prior hour. He’d called it “bear brush”, and it was apparent that he really thought there was a bear in it. He was acting like 180 lbs. of bait, standing downwind in the 15 MPH breeze so the bear could smell him. He’d guaranteed that the bear would be able to smell him, as he’d been too busy chasing dudes like me all over the Alaska Peninsula to take a bath for the past two weeks.

He was getting really crazy. He’d unbuttoned his coat, and grabbing the skirts, had thrown his arms wide, opening his armpits to the breeze, giving the wind a good chance to carry his scent to the bear. He turned this way and that, bowed and pirouetted. Then he started to dance, prancing up on one foot then the other, doing a little hop-skip slapstick in the tundra, I could see him grinning hugely as he did his act. I could see that he was just fooling around, and there wasn’t a chance of there being a bear in that patch.

I had thought he was truly serious about a bear being in that brush patch, especially after he took off downhill, going down and around and into the wind to put himself below and upwind of the patch and presumably of the bear. What with the dance and slapstick I could see that there wasn’t the chance of a snowball in hell that there was a bear in there. I watched him prance around for a minute, almost expecting him to break out in song.

I leaned forward to rest my sore knee, throwing my weight on the prototype Super 91 muzzleloading rifle that I’d designed and built just for this hunt. It was the first .50 (504) caliber Super 91 produced by the company named after me, White Muzzleloading Systems. I had started designing a straight pull muzzleloading action in the early 70’s, borrowing liberally from J S Paully, Druese, Mauser and the Springfield ’03 to create a unique straight pull in-line rifle, finally finishing the project in the late 80’s when the muzzleloading market showed that it was being driven by muzzleloading hunting. In-line muzzleloading rifles had become popular in the meantime. I’d combined the new action with the long bullet slip-fit technology pioneered by Joseph Whitworth and Rigby in the 1850’s, into what I called the “White Shooting System”

I was able to put together a quite elegant rifle with many sophisticated and distinctive features. To my surprise, the Super 91 was a hit, and after making a number in my spare time (I fool with rifles and tooling while waiting for the phone to ring), and selling them to friends, I organized and incorporated White Muzzlleloading Systems. We have been manufacturing them since the summer of 1991.

Looking back, I consider it amazing that Pauley thought up the in-line action only four years after Forsyth had invented the percussion system in 1808 and 3 years before Joshua Shaw invented the percussion cap and nipple that we all use today. Whitworth was likewise a genius, staying far ahead of his time. The Whitworth bullet of 1853 was 3-3 1/2 times longer than its bore diameter, in a day when the round ball was the reigning projectile and when Minie’s, Pritchett’s and Burton’s bullets were just aborning. It would be another 7 years before the short Minie ball was tested in the American Civil War.

Unfortunately, cartridges came along with the Civil War and Whitworth’s advanced bullets were forgotten, at least to muzlleloading. But they were remembered by the designers of the long, powerful cartridges used in later single shot rifles. By 1870, Rigby and other English gunmakers had revised Whitworth’s concept of a hexagon bullet to a bullet of round cross-section, fired in a relatively fast twist, shallow groove bore. Amazingly, the barrels look much the same as modern barrels and to my great delight, proved to be manufacturable using modern technology. I found they shot terrifically well, far better than any round ball and significantly better than the modern Minie and Maxie balls.

Some pretty large animals had fallen to my early experimental rifles and long bullets, including a good 60-inch moose. The early Super 91’s that I built were 41 (410) or 45 (451) caliber, throwing a long SUPERSLUG, as I’d named them, sized to just barely fit the land-to-land diameter of the barrel. I’d just barely finished developing a 50 (504) caliber barrel and bullet (the 50 means the caliber is nominally 50, the 504 is the land-to-land diameter of the barrel) but hadn’t yet built a Super 91 for it until the night before this Alaskan brown bear hunt was to start.

I had actually scheduled the hunt some 5 years before. I had hunted for caribou out of Dick Gunloggson’s camp in 1985 , fell in love with that wild country and swore to come back. Eventually, I scrounged up enough money for a down payment on a brown bear hunt. I waited out the time for the bear hunt impatiently, keeping busy with my medical practice in Roosevelt, Utah, and working on the prototypes of the rifle that eventually became the Super 91.

Meantime the bear hunt was getting closer and closer. I had planned on taking either a fine Model 70, 375 H&H Magnum straight-tapered barrel rifle I love or a .416 Taylor that I’d previously built., On the day before the airplane was to leave, Dick Cheney, who did subcontracting for the company, called and asked if I wasn’t going to take a Super 91. I replied, “I don’t have a 504 caliber ready to go” and explained that if I took a Super 91, I’d want to take a .504 with the big 600 grain Superslug. I’d found that the big 600 grain Superslug shot wonderfully well with 150 grains of Black powder, producing better than 3000 ft lbs of energy at the muzzle and slowing less then 150 FPS per hundred yards. Dick then informed me that he had a prototype Super 91 action on hand with a prototype 504 barrel mounted, and he insisted on bringing it up from SLC so I could take it with me.

Well, he didn’t show at 2 pm, or even 5 pm. He finally showed up at 11 pm, just one hour prior to midnight. Now I was stuck. I had the 416 Taylor ready to go, but was now enthused to take the .504 too. At least I had the night off and didn’t have to leave for SLC and the airport until 4 am the next day.

Can you believe that I stayed up the whole night working on that cussed rifle. By 2 a.m. I had the rifle assembled and the action assembly working smoothly. This was no production rifle, but a true prototype that needed all the bugs worked out and lots of hand work and close attention to detail. The stock was inletted and the glass was hardening by 3 a.m. It would have to finish hardening on the plane. I hoped the cold in the aircraft would not impede its strength. I mounted a Leopold 1 3/4-5 scope on Weaver bases and bore sighted the rifle at 4 am. There was no time for traditional finishes so I ended up painting the action and barrel a metallic brown, and spraying the stock black with fast drying undercoat and epoxy enamel. It was still drying when I left the house for the 2 hour drive to the airport in SLC. When I stepped on the 737, I hadn’t shot it, let alone sighted it in. And I hadn’t had any sleep either.

My flight plan called for en evenings layover in Anchorage. I had been stationed at Fort Richardson, just north of Anchorage, in the late sixties for two years as a guest of Uncle Sam. We had an acre sized lot with a small house on McCarry road. The local shooting range was located at Eagle River, run by an old man I got to know well. I planned on using the layover to sight in the Super-91.

Lo and behold, the old house on McCarry road was gone, replaced by an apartment complex. So was the shooting range, replaced by a housing subdivision. The new shooting range was way out in Alyeska, a 40 minute drive down the Turnagin Hiway. There wasn’t time to get to the range and shoot, so I spent the layover mostly sleeping. I ended up on the plane to Cold Bay without having fired the rifle.

Cold Bay is just exactly that. The rain there is normally horizontal, the winds are usually awful and they were again. Dick Gunloggson met me there with his Cessna 180 and we made the 90 mile flight to his David River camp before dark. Once again, no shooting or sighting in was done.

I mentioned to Dick that I’d not been able to sight in my rifle. He merely commented on the large number of bear hunters who turn up with guns not quite sighted in and said that there would be a sighting in session next day before anyone left camp. I got the idea that the session would give him an idea about who could shoot and who couldn’t. This information might help him decide who went with what guide.

The food at Gunloggson’s camp was exquisite. It was almost worth the tab just to experience it. We feasted on salmon and caribou and Ptarmigan that night , while we regaled each with lots of lies.

Next morning we were up and shooting early. Most of the hunters had 375’s, while one sported a 404 Westley Richards, an enormous cartridge with awesome power. I had brought along 30 charges of 150 grains ffg black powder in flip-top plastic canisters. I decided to devote 15 for sighting in and save 15 for the bear. My 416 Taylor was already nicely sighted in and I decided not to worry about it.

I shot my proto Super 91 last, knowing that I would need the most time. I quickly found that there wasn’t much difference in recoil between the big modern rifles and my 50(504) Super 91. I was delighted when the rifle fired a nice 3 inch group coming in 2 inches high at 100 yards with my 150 grain black powder load, but wasn’t at all delighted to find that the scope touched my eyebrow with just about every shot. I reminded myself to be careful. Sure as shootin’, I would forget all about it in the excitement of the moment and bust myself between the eyes.

Taciturn as ever, Dick Gunlossosn just grunted after he saw the shooting and heard that big 600 grain bullet whump when it hit his back stop. He said he couldn’t see any reason not to use the Super 91 on a bear. It looked to him like it “could kill on either end.”

Late that afternoon, he packed me into his Maule S-4 Skyrocket and we flew off for spike camp. It wasn’t far away. actually just over the hill and down the country a little. Dick landed on one of those bare, flat places between patches of brush and tundra that seem to pop up in this country, to the delight of bush pilots and hunters, and dumped me out. There wasn’t a place higher than 100 feet off the ocean. A good big wave would have washed the whole place away.

There I met my guide, handsome, cheerful 32 year old Pat McCullom, who turned out to be one of the outstanding outdoorsmen and guides of my career. He was raised in Idaho, had been in Alaska for the past 4 years and intended to stay forever.

When I announced my intentions of taking a bear with a muzzleloader, something that I anticipated would cause some trepidation, he was thrilled and excited. It turned out that he was an ardent bowhunter and had some impressive stories of Alaskan hunts, including the big bears.

We spent the evening getting better acquainted and telling stories of past hunts and tight situations. Both of us had pictures of past hunts and we enjoyed each other thoroughly. He even turned out to be a better than passable cook, an attribute rarely found in the young, and we enjoyed ptarmigan pilaf that night.

Camp was located well down in a deep gully out of the near constant wind. A small but thigh deep creek meandered past it, providing drinking and bathing water. There were no salmon in it, so it should have been bear free. This proved not to be the case. On our second night, we were awakened by snorts and huffs, then a big body bumped the tent. Pat whacked the canvas and yelled, “Git.” There was a startled guttural ‘woof’ and a gigantic splash as the bear hit the water, followed by grunts and splashes rapidly receding in the distance. Pat turned over and was snoring in a minute. I stayed awake, rifle at fingertips , but finally dozed off when Mr. Bruin did not return. There were footprints big enough to fit my size 13 waders plus an inch all around beside the tent come morning. “May be a ten footer” said Pat as we left camp. “Just middle sized.”

Early next morning, long before dawn broke the horizon, we climbed the nearest hill behind camp. It was here that I learned he reason for the hip length waders demanded by Gunlogson. We had to wade the thigh deep creek next to camp, only to wade a calf deep slough to reach the hill. This kind of thing was to be repeated many times over the next few days.

The increasing light of day revealed a beautiful sight. The Pacific ocean was visible, looking to be 6-8 miles to the South. The Pavlov volcano raised its head to the North, and off to the East were the impossibly steep Pinnacles. Between us and the Pavlov was the bear country. The Pavlov was an active volcano, though it hadn’t erupted for 100 years or so, and provided a warm place for hibernation. The countryside was broken, every gully running water, and every tiny creek full of salmon during the July- September run. It was the salmon and the Pavlov that made living so fat for the bear.

Pat explained that we would spot for bear working the streams from the nearby hill, then walk up the promising ones. I discovered from Pat that the bears were mostly nocturnal. They would feed during the night, then lie up with a full belly during the day. Indeed, most of the bear we saw through the spotting scope were coming off the water and heading towards convenient patches of brush.

We spotted bear almost immediately, with as many as a half dozen in view at a time. One smallish bear made the trip from the horizon, down across hill and gully to end up almost at our feet. I learned the fallacy about the bear’s poor eyesight with that one. This bear spotted us outlined against the sky on the hill-top from a full 300 yards , turned and ran as hard as he could go all the way back the way he came, demonstrating the tremendous endurance for which they are so famous.

Wading the creek and climbing the hill would become a familiar routine, spotting for bear until usually about ten o’clock, breakfasting, then walking 4-5 miles through tundra and slough to size up the interesting ones. There was no shortage of bear, although not all of them stayed in place long enough for us to find them. To my disappointment, all we saw were ugly, dark brown critters, some small, some bigger. I explained to Pat that I had already taken a big dark bear with a modern rifle. This time I wanted a light colored bear, preferably a blonde, and would be willing to trade size for color.

Over the next several days we inspected plenty of bear, but could not find the one I wanted. We looked at many of them close up but none were the blonde that I wanted. Pat turned out to be as good a guide as a dud could ever want. He was kind, helpful and solicitous. When my arthritis flared up due to the tundra crawling, he slowed his pace without complaining and made sure I got lots of rest without making it obvious that I was the problem. He made sure I took my arthritis medication, fussing over my sore joints like a mother hen.

The weather was as nice as Pat had ever seen in the Peninsula, cloud cover about 40% and wind never worse than ten knots, but by the fourth day the weather was picking up, and it looked like a return to normal lousy conditions. We had seen two big bear that morning and one had looked blonder than usual. That got my hopes up. They were a ridge further away then the ones we has so far pursued, so I took an extra pill and we went after them.

We were in bear country by noon, after a 4 hour hike, what with stops for rest and checking on likely spots where we might accidentally find a bear. The creeks were low and the salmon fewer than expected. The end of the run was in sight. Snow was well down on the flanks of the Pavlov, a harbinger of nasty weather, cold and hibernation. Small bands of caribou moved here and there. A wolf howled and was answered from far away.

Finding a bear spotted from the hill behind camp was not as easy as it sounds. It was a long hike to the bear, so we could only hunt down one or maybe two a day. Identifying the hillside and the particular patch of brush that held bear was chancey. After you got there, all the patches looked the same. We were forced to stalk every hillside and brush patch, approaching from downwind, in an effort to see the bear before he saw us. Mostly this meant sneaking up on a house sized patch of ‘bear brush’, carefully looking it over, then even more carefully examining every nook and cranny with binoculars for hair, nose, claws or whatever other clue a sleeping bear might present. If that didn’t work, then we would stand out in plain sight and start a loud conversation, telling old jokes and stories, hoping the bear would awaken, stand up and take a look.

We’d seen the blondish bear go into a doubled patch of brush, each one twice as big as a house, on a steep hillside. We planned our stalk to came out upwind on a small knoll, maybe 15 yards from and above the edge of the brush. By craning our heads overt he edge we could see fairly well into the brush. Unfortunately, it wasn’t good enough to see the blonde bear. We finally got up on hands and knees and glassed the brush, but still couldn’t see anything. It was quiet except for the wind noises.

A fair blow was up by this time, about 15-20 knots out of the west. Finally, Pat stood up and started talking. We conversed in soft tones while we glassed the brush. Still nothing, though Pat felt pretty sure that the bear was still there. We just couldn’t see it. The brush looked pretty deep with lots of low places that would hide a big bear. We increased the volume of our talking, almost shouting into the wind, but that got no result either.

Pat shifted his 375 to his shoulder and said, “That bear is still there. I’m sure of it. I’m going to go down and around and get downwind of him and give him a smell. I’m so rank after not having a bath the last two weeks that the stench will drive him out of that patch of brush for sure.”

This was startling. After all, he was the back up. “Hey,” I protested, “that’ll leave me up here with just a single shot” He patted me on the shoulder as if I was a little kid, “I’ll be OK,” he stated, “Don’t worry” Good heavens, the man thought I was worried about him! I wondered how red my face was.

He skirted the brush patch by 50 yards as he headed downhill. I stood there, watching him go. Then deciding that preparation was the better part of valor, I laid two of my Quickchargers loaded with 150 grains of FFG Blackpowder and 600 grain SuperSlugs on my gloves. I knelt down by them, watching as Pat made a broad turn and started back up the hill towards me. He reached the bottom of the brush and eventually launched into his slapstick dance, arms akimbo, as I have already related.

I relaxed and laughed. Obviously there was no bear, otherwise that fool guide wouldn’t be doing slapstick with his rifle as his feet. Suddenly there was a snort, then a crash and a bang, then a series of snaps and pops. A big blond head reared up out of the brush, snapped a look at the dancing Pat and disappeared.

The crashing got serious all of a sudden, the obvious sound of a very large body slapping through brush. There were tooth grinding sounds, too, and huffs and puffs and all sorts of scary noises. An enormous animal burst out of the brush 20 yards from me, headed out into the tundra and quartering away a little. It was running like a rabbit, belly to the ground, 30 feet at a bounce, but it was the biggest rabbit I’d ever seen — and it was blonde. Marilyn Monroe couldn’t have looked better. It was the bear I’d been looking for. Not as big as some, but who gives a damn, it was the right color.

Suddenly, and without any conscious effort, I was seeing the running bear through the scope of my Super 91. The crosshairs seemed to automatically rise, center & lead the bear about three feet in front of its nose. I suffered a fleeting thought. “What the hell are you doing shooting a muzzleloader at a running bear?” And the gun went off. All by itself. The damn scope banged me square in the forehead, not that I cared any or even noticed, and the big 600 grain Superslug made a horrific “whump” as it smacked the bear in the rear ribs, angling towards the opposite shoulder. Blood ran down my face.

Looking past the scope and recovering from the recoil, I saw the bear slew into a 270 degree turn, then tumble and roll. It came up running, but had a hurtful gait that rapidly slowed. My hands seemingly acted on their own, dumping a load of black powder down the barrel and following it with a Superslug. All that practice was paying off. I rammed it down the barrel as the bear slewed to a stop, then turned and sat, sitting in the tundra like a big dog. I thought I was in for it, what with the bear eyeing me across 70 yards of tundra as I reloaded.

I could hear something screaming, mixed with bellows of despair. I thought briefly it was the bear, or even me, as I have been known to make funny sounds when I get excited, then realized it was Pat. He couldn’t see thing, down the hill and behind the brush as he was, and he was sure that his carefully guarded dude was dinner.

By the time this thought passed, I had capped the rifle and sent a second shot into the bear, centering the chest with the crosshairs. Damn scope hit me again. More blood in the face.

[one_half] [/one_half]

[/one_half]

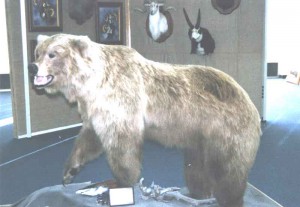

[one_half_last]Not the biggest bear in the world, but the right color. I still carry the scar from the shooting, right square between the eyes.[/one_half_last]

When I recovered from the shot the bear was down and not moving. Pat was behind me by then. We gave the bear a few minutes, I wiped off my face, reloaded the Super 91, then we walked up carefully, approaching the animal from the rear. The bear turned out to be a sow, as pretty a bear as I’ve ever seen. Her coat was abnormally long and fine, and as blonde as these bears ever get. She wasn’t awfully old but was bigger than I could reach around and a lot longer than I was tall.

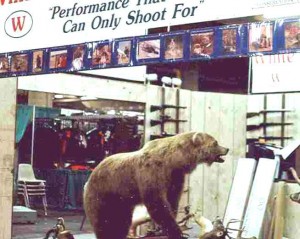

I sat down by her and stroked her head as if she was one of my kids. I thanked her for her sacrifice. (This may sound a bit crazy to an Anglo, but a Ute friend that I admire taught me great respect for those that lose their precious lives for out benefit) I promised her that she would be well taken of and that she would occupy a place of honor where many could enjoy her for years to come. (So it has been. She has been admired by countless thousands at SHOT and other hunting shows across the country. Every day, she is carefully placed out in plain sight, in front of the White Rifles factory where all can see her. She is the handsomest bear I know of)

[one_half] [/one_half][one_half_last]

[/one_half][one_half_last] [/one_half_last]

[/one_half_last]

[one_half]Left: Katy in the Roosevelt, Utah showroom. [/one_half][one_half_last]Right: Getting ready for the SHOT show, 1996[/one_half_last]

Pat was thrilled. He immediately pronounced her to be far larger, fiercer and heavier than she really was. Guides are like that. They want their dudes to feel like heroes. He was such a fine guy that I couldn’t object, only chuckle at his trying to bolster my ego, which I have a hard time trying to keep within bounds anyway.

We found that both 600 grain bullets had gone all the way through. The first had struck just to the rear of the ribs and exploded the liver then messed up some lung as it angled slightly to the front. The liver was blown literally to pieces. The second shot had gone through the heart as it angled through both lungs, exiting behind the last rib, but it was clear that the killing shot was the one through the liver, causing quick and massive hemorrhage.

I was sorely disappointed. I had wanted to collect a 600 grain Superslug from the animal to use for advertising and both bullets were lost in the tundra. Pat offered a solution, “I’ve never seen bullets go all the way through a bear end to end. Shoot her in the butt. Aim at her off shoulder and we’ll catch us a bullet.”

That seemed reasonable, so I calculated where the underneath shoulder was, and angled a last shot through her. We turned her, only to discover a huge gaping hole where the ball joint of the shoulder should have been. I had managed to center it exactly and had blown the whole thing out through the hide

“I’ll be damned.” Pat said. “That huge bullet went all the way through. And blew out the shoulder joint. That was a real smart suggestion I made.” He was thinking of the repair work that would have to be done now to fix the hide.

We went to work in the waning hours of the day, taking off head and paws with the hide. Pat packed it all up, a huge load, roped it to his packframe and still outwalked me despite the heavy load. At least I got to carry his rifle.

We got back to camp with the setting sun, and just in time to catch a snowstorm. Sure enough the weather was taking a turn for the worse. It snowed and blew while we worked on the hide, paws and head all the next day, salting down the hide, splitting the lips and ears and getting it ready for the taxidermist.

Gunloggson flew in the next day, bringing word of worsening weather to come. Two days later, after gorging on Dick’s good food and enjoying the company, we flew back to Cold Bay in the teeth of a fall storm.

When the plane left, the rain was once again horizontal.

Good Hunting

DOC