ON COOPER’S MOUNTAIN

1966

The spotting scope had been set up for an hour, but for the bigger part of that hour had canted crazily to the sky while I lay back on a moss covered bank enjoying the decidedly pleasant mid-morning Alaskan sunshine. The sunshine was unusually welcome as only an Alaskan can testify, because the long artic winter was over and Breakup was at hand, A warm Chinook wind had been gently blowing since the weekend past, melting snow and ice and breaking the grip of winter on the land. Indeed, that warm sun had instilled my winter-chilled carcass with enough ambition for a spring bear hunt, which was the excuse I gave my wife as I left with Dave Wiley for Cooper’s Mountain on the Alaska Penninsula.

My wandering on thoughts touched on Wiley for a moment. Only man on the Post crazy enough to come on a crazy trip in the middle of Breakup. Only a sure ’nuff Cheechako would launch his spring safari for bear in the middle of Spring Break-up.

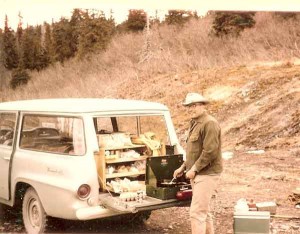

Here I am using the spotting scope from the truck. My daughter called that International, ‘the Friendly Monster’. This is Alaska, at the foot of Cooper’s Mountain, on the shores of Kenai Lake, Spring,1966.

Here I am using the spotting scope from the truck. My daughter called that International, ‘the Friendly Monster’. This is Alaska, at the foot of Cooper’s Mountain, on the shores of Kenai Lake, Spring,1966.

I opened a shuttered eyelid, spotting Wiley bent over the tailgate of the “Cornbinder,” as I called my 4 x 4 International Travelall, busily doing something with a Coleman stove which I knew would turn out delectable. I contentedly settled back to doze, only to jerk awake at a wild shout from the truck.

“Bear! Bear!!,” bellowed the noise. I sat bolt upright expecting that a bruin had come to rob Wiley of my breakfast. (Egad-What a catastrophe.) “Bear!” Wiley shouted, “Up on the hill” and he waved his spatula at the hillside that I was supposed to have been watching.

I scrubbed the sleep out of my eyes and squinted against the midmorning brightness at Cooper’s Mountain, near a mile away and plastered with melting snow. Sure enough, there was a black speck which could only be a bear newly emerged from his den. Heaving to my feet, I snatched up the spotting scope and righted it. My first glimpse told me that we had our bear in sight. It looked like a big black one, moseying slowly along the hillside, way above timberline, nipping at old grass and berries left from last year’s crop.

Wiley was already at the truck, putting on gear and loading his Enfield 30-06. He was a Regular Army captain, commanding the Medical Service Corps unit for the 30th Artillery, of which I was the surgeon. We were stationed at Fort Richardson , near Anchorage , Alaska . Wiley had already demonstrated his ready willingness to tackle any job or task and I knew only too well that we would soon be heading up that steep snows lick slope.Wiley cooks up breakfast on the tailgate of The Friendly Monster. We killed a bear for him a week later from the same location, with me being the guide and packer.

Wiley was already at the truck, putting on gear and loading his Enfield 30-06. He was a Regular Army captain, commanding the Medical Service Corps unit for the 30th Artillery, of which I was the surgeon. We were stationed at Fort Richardson , near Anchorage , Alaska . Wiley had already demonstrated his ready willingness to tackle any job or task and I knew only too well that we would soon be heading up that steep snows lick slope.Wiley cooks up breakfast on the tailgate of The Friendly Monster. We killed a bear for him a week later from the same location, with me being the guide and packer.

“What a way to spend Memorial Day,” I commented, “traipsing through all that snow. You sure you want to tackle it ?”

“Sure as shootin’” was the reply, complete with ready grin. I grabbed a packrack out of the truck, quickly checking the wet-gear and grub packed in it. I threw in an extra length of rope and grubbed out a half box of the finger long cartridges that fit my 450-3 1/4 double rifle. I found the rifle next and swung the action open with the under-lever to check the barrels, then dropped in two of the hand loads that I had carefu1ly assembled just the night before.

The gun was a treasure that I had picked up from a close friend mainly because he found the recoil too much for his tender shoulder. The 3 1/4 inch long case swallowed 120 grains of FFg black powder under a 330 grain hollow point bullet cast of 1110 tin-lead mixture. My chronograph had shown that this load would develop 1650 fps at the muzzle with 2220 ft. 1bs. of energy and that the barrels both shot into a rough 4-inch group at 100 yards. It had been handmade by Wilkinson and Grey of London in about 1880 and was the epitome of fine English gun craftsmanship. Its top barrel flat even bragged that it had been manufactured with Metford rifling, once greatly acclaimed for superior accuracy.

Wiley was already well up the track leading from the bank of Cooper’s Lake , where we were camped, to the slopes of Cooper’s Mountain. I snatched a handful of candy bars and followed, stumbling and sliding in the muck and mud underfoot.

Inside of ten minutes we were both wet to the knees from the heavy brush, and within twenty were wet to the crotch from the hip-deep drifts of melting snow that more resembled giant slush cones than snowbanks. There wasn’t a spot of dry ground on the whole hillside. Water was ankle deep where we stepped and deeper if we weren’t careful about where we put a foot. And the higher we went, the deeper and more frequent the drifts became.

Needless to say, our progress was slow and painful. After mushing up the slope for an hour, we spotted the bear again, surprisingly in about the same place that we’d seen him before. We were nearly at the timber line by then, and were running out of cover. Worse, the weather had deteriorated, with a sharp wind and scudding clouds that conglomerated over the next hour, covering the once blue sky with a solid gray Alaskan overcast.

Now we were cold as well as wet, and the climbing was getting tougher. We would climb over some of the drifts, but others would cave in under us, floundering us in hip deep piles of icy slush from which we would then have to wade or climb, only to fall in again at the next step.

Noon passed, but we stayed with the climb. The bear would appear on the slope from time to time as we climbed to a vantage point, but most of the time was hidden from view. The sullen overcast finally dropped low enough to hide the top of Cooper’s Mountain, and further chances of seeing the bear disappeared.

“Ready to give up?” asked Wiley, that challenging grin on his face.

“I’m as ready as you are,” I answered, knowing full well that he was just as tired and cold as 1 was, but not ready to admit it. And I wasn’t about to admit that I could take less than he could.

“Toss you for the shot?” he queried mischieviously, dragging a quarter out of his pocket. 1 knew he’d brought it along purposefully to challenge me with. He threw it in the air.

“Heads,” I said, “and go jump in Cooper’s Lake .”

Wiley groaned aloud in mock anguish. “Heads it is. Guess the first shot is yours. So’s the decision to tackle that hill. You want that first shot bad enough to do it?”

I sighed, wiggling my soaked fanny in the slushy snowbank I was sitting on. I couldn’t have been any wetter and had sat down. “Yes,” I decided, “let’s take the chance. We’re close enough to the top now that we might be able to see him from up there.” Wiley struggled to his feet and I followed, adjusting my pack as we slopped along, feet squishing in the water and slush underfoot.

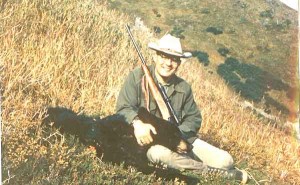

Double barreled under-lever rifle by Wilkenson & Gray, London, in 450-3 1/4 caliber. The 3 1/4 inch case holds 120 grains of Black Powder and throws a 330 grain hollow point bullet at 1650 FPS. The photo is backwards.

Double barreled under-lever rifle by Wilkenson & Gray, London, in 450-3 1/4 caliber. The 3 1/4 inch case holds 120 grains of Black Powder and throws a 330 grain hollow point bullet at 1650 FPS. The photo is backwards.

The lower slopes had been covered with grass under the snow, but the snow-slick grass was now changing to tundra, which was much easier to walk in. We sank up to our ankles with each step but it was more restful than slipping and sliding on last year’s snow-slick grass. A fine snow was starting to fall and we were high enough that foggy banks of mist obscured the landscape. The higher we went, the thicker the soup became, and soon we could see little further than 50 yards in any direction.

Wiley huffed to stop and collapsed on the tundra. I cast a wary glance all around but could see nothing except gray cloud. We had seen a huge sow Brown bear on this mountain in the past and knew we could run into her anytime. This high, the fog even blanked out Cooper’s Lake and the tough trail we had followed.

Wiley spoke in a whisper, “Wonder where that bear is?” He rolled over on his belly so he could watch the slopes immediately above us. “He ought to be around somewhere close. He was moving this direction, so let’s move up into the rocks and sit. Maybe he’ll walk into us.”

I nodded in assent, and we struck out up the hill towards some rocky cliffs we had seen earlier. We figured that his den would be close and we would be in a position to intercept him when he returned.

A little breeze sprang up, scudding the heavy mist from the direction the bear presumably would come from. “Good thing,” I thought, “or the bear would get our scent for sure.” I was climbing quietly, trying not to make much noise in the sloppy tundra. It was tiring work and my thighs were burning with the fire of overexertion. I suddenly realized that Wiley had disappeared. I glanced to the left only to find him on his belly in the tundra, attention riveted up-slope and hands fumbling with his ’06.

My eyes automatically flicked up hill, zeroing in on the object of his rapt attention – a bear, black as midnight , ambling slowly from the direction we expected him and about 70 yards away.

I promptly fell flat on my face in the tundra, gasping with exertion and surprise. I tried to catch a good lungful of air as I shrugged the double rifle off my shoulder. Another look showed the bear still unalarmed but breaking into a thick bank of soupy mist. Without much conscious volition, the 450-3¼ came up, the right hammer cocked. I caught the fore-shoulder of the bear through the open sights and the rifle slammed back, its boom dulled to a solid thud by the all enclosing mist.

Well, it turned out that the bear wasn’t all that big after all, but then any bear you get after a hike up Cooper’s Mountain in butt-deep snow is a real trophy. After hunting with round ball muzzleloaders for years before this hunt, I can understand why the hunters of yesteryear switched to the then new cartridge guns so quickly. It wasn’t just the fast reloading, it was also the effectiveness of the elongated bullet with a hollow point. There was no way that the rifle could have been more deadly than it was.

Well, it turned out that the bear wasn’t all that big after all, but then any bear you get after a hike up Cooper’s Mountain in butt-deep snow is a real trophy. After hunting with round ball muzzleloaders for years before this hunt, I can understand why the hunters of yesteryear switched to the then new cartridge guns so quickly. It wasn’t just the fast reloading, it was also the effectiveness of the elongated bullet with a hollow point. There was no way that the rifle could have been more deadly than it was.

The bear collapsed and came thumping down the steep slope. I found myself half-standing, left hammer cocked and sights on the black form as it rolled to a stop about 15 feet away.

“I don’t think you need a follow-up shot,” commented a wry voice behind me,” That big bullet took him square through the shoulder and chest. He didn’t even know what hit him.”

And so it appeared. The big 365 grain hollow point had broken the bear down with a hit in the shoulder joint, then had penetrated the chest, rupturing the lungs and great vessels of the heart before exiting behind the up-slope shoulder. It had obviously been a quick and merciful kill.

I flopped down by the bear while Wiley quickly snapped some pictures, then we skinned the animal, taking the paws and head intact. We would carefully skin them out later when there was more time and comfort.

We found the bear to be a barren sow, about three years old, thin and skinny from her winter’s denning, but with a thick, black glossy coat. We didn’t forget to harvest the filet, backstrap and hindquarters, knowing that they would be tasty eating after a winter’s tenderizing inactivity.

As we were stumbling down the hill, wet, cold, tired and with a long hike ahead of us, Wiley asked, “Hey White, you ready to come back next week-end for my bear?”

“Not in the middle of Breakup, you lummox,” I answered. “It’s going to take all summer to warm up after this hike. You’re a glutton for punishment, that’s for sure.”

“So are you, friend,” he said, chuckling as he waded into a fresh snowbank. “See you up here next week.”

Here’s Wiley with the bear he killed the next week. All the snow is gone now but the mountain is just as steep .

Here’s Wiley with the bear he killed the next week. All the snow is gone now but the mountain is just as steep .