1974

The morning air was cool. Cool to the point of being sharp. And it was still. It had frosted a couple of mornings before after a late season high had moved into the area. There was no wind, very little breeze, just right for sitting a long time without spreading scent far downwind. It had been light for some time, but the morning sun had not yet peeped over the high mountain tops to the East. If I glanced uphill I could see the edge of shadow creeping down Blue Mountain to where I sat, but it looked to be 10-15 minutes before it would high-light my hiding place, Still, I found it light enough to shoot when I checked the sights of my “Gemmer-Springfield” against the dark pines across from me.

I had reached the little nook I was crowded into by following the footsteps of Paul Mantz, “Runner”, to those of us wise to his habit of charging up and down mountainsides. He made it look easy, loping off through the sage and pine, whilst the rest of us stumbled and sweated and cursed behind. This morning had been no exception, the trip up Blue Mountain being made in the dark, with just a single flashlight for illumination.

Paul Mantz. ‘Runner’ to most of us, at another time and place, with a Utah antelope and a percussion Hawken repro. Yes, he really dresses like this when he hunts. Lives in a log cabin, too.

Paul Mantz. ‘Runner’ to most of us, at another time and place, with a Utah antelope and a percussion Hawken repro. Yes, he really dresses like this when he hunts. Lives in a log cabin, too.

Being naturally endowed with an excess of adipose and not being inclined to exercise, at least enough to keep me in shape for such fool doings, I fell to the rear of the party struggling up the slope, huffing and stumbling along, carrying that heavy rifle, trying to keep Runner and his light in my front. When there was a murmured protest at the speed of the climb, he had the guts to command, “Quiet”, “You’ll scare the game. Quiet”.

Believe me, that hillside was mighty steep. We climbed steadily for an hour before “Runner” slowed enough for the rear guard to catch up. The morning was just beginning to break as he faced about, long flintlock Hawken in hand, and directed us toward our various perches

On the steep mountainside. He finally whispered “Doc” and pointed up a precipitous hillside just beginning to show in the gloom. It was still near dark as the inside of a cow, as I clambered up, trying to pick out the game trails, more by feel than sight, and trying to be quiet, all at the same time.

I recalled., as the salt sweat stung my eyes, that Paul had described an early morning sit for big buck mule deer, and nothing said about the strain of getting there. I guess I had unconsciously suppressed the question at the time, probably knowing better than to ask. According to “Runner’, the biggest bucks in four counties lived on this mountain, and just naturally would head for its tallest peak when the shooting and banging and human noise of “Opening Day” started. The trick was to be on top of the mountain before all the commotion started, in position to bounce a big buck as he hurried to the protection of the heavy timber.

He’d made it sound like the perfect black powder hunt. ..sit still and let the deer come to you. No long walking and no long shooting. Shots likely to be right close, enough so that an open sighted, heavy bored round ball rifle would be just the ticket.

So it was that “Runner” carried a flintlock “Hawken” full stock in 54 caliber, one he”d built himself following the accepted conception of what an early fur trade mountain rifle might look like. The others carried a miscellany of muzzle loading rifles.

Me, I was cheating. I wasn’t packing a muzzle loader at all, as I had done for so many years. For the first time in I don’t know how long, I was toting a breech-loading rifle. Seems as though Ed Trump had just finished up the prototype for the Gemmer-Springfield series that was then being considered for production by Green River Rifleworks. (1974) The gun never did get into even semi-production, and only a few were eventually built. This one was so new it hadn’t even been browned, though the original Springfield trapdoor action still had blue on it. The stock was stained and oiled, but the metal was bright.

A trapdoor surplus military action, with a thick octagon barrel complete with rib and ramrod, assembled in typically Hawken fashion. Who would have thought of it other than Gemmer. He was the young gunsmith-entrepreneur who eventually took over the Hawken Brother’s business in St. Louis, long after the death of the fur trade and well into the demise of the muzzle loader. By his time the heyday of the heavy calibered Hawken mountain rifle was done. Single shot breech loaders were commonly available and the lever action repeater wasn’t far off.

The military was surplusing excess Springfield trapdoor actions even then, and several firms, Gemmer among them, made it their business to offer fancy sporting rifles based on the surplus actions. Gemmer’s competition produced rifles looking much like the ‘officers model’ Springfield carbine, usually with checkering and pistol grip. Gemmer was the only one to produce a rifle that looked very much like the old Hawken Mountain rifle (only a few are known) and I can imagine that it proved popular with the old mountain men.

It certainly hit me just right. I was bodily taken by it, being well bitten by the Hawken bug, and especially appreciating the ramrod (once stuck a shell casing in a trapdoor carbine whilst a whole herd of bucks stared at me — no ramrod) I also very much liked the old 45/70 caliber, already being in possession of innumerable cases and bullets plus a set of reloading dies. It was about the only “modern” caliber I ever shot at that time.

Over the years, my favorite load had evolved into 75 grains ffg Black powder tightly compressed under Lyman’s 365 gr. cast hollow point bullet. It’s accurate in most 1:20 twist rifles, velocity is excellent (about 1400 fps) and it’s very easy to load — the case holds just exactly 75 grains, level full.

So it was that my pockets were full of fat brass cartridges and my hands full of a handsome copy of Gemmer’s best sporting rifle. I finally found a place to sit. It overlooked a huge steep sided slope covered with sage and buckbrush and bordered by mixed quakies and pines.

The mountain that we’ d climbed extended on steeply downward, deep blue in the distance and dark of the brightening morning. The others had long disappeared from where we’d separated below. The conjoined edge of shadow and sunlight crept past, lighting the deep shadows beneath pine and quakies and heating the silent slope. I was soon out of my down jacket, throwing it down in the bunch grass between two deep swatches of “buckbrush and throwing myself down on it.

‘Runner’ with his son Kip at the end of a a long day hunting Utah mule deer. Those deer were dragged off the mountain whole. It was steep enough that we could point them downhill, give them a kick and catch them at the bottom. Well, almost.

‘Runner’ with his son Kip at the end of a a long day hunting Utah mule deer. Those deer were dragged off the mountain whole. It was steep enough that we could point them downhill, give them a kick and catch them at the bottom. Well, almost.

I checked the Gemmer, making sure the hammer was at half-cock and the DST unset.

I put two fat cartridges between the fingers of my left hand, and began the meticulous search that would eventually spot a buck standing back in some shadowed nook, he studying the hillside for danger signs, just as I studied it for him.

I knew from experience that just waiting for a buck to appear would not do. Generally when a buck shows himself it’s only after a studied perusal of his surroundings, then a sudden dash to the next safe haven he’s picked. I didn’t want to shoot at a running buck, and would have to turn down such an opportunity, unless he practically ran me over. Instead, I tried to spot him first, before the dash to safety even started, first locating the copses of brush and trees, the turns of hillside and gully, the vagarities of topography that a wise old deer would take advantage of.

I used my 7 x 35 pocket binocs to study each place in turn, sweeping from left to right, then back over the same route, moving head and arms slowly to avoid attracting the gaze of a wary buck. At the same time, I listened behind me, trying to separate the quick movement of birds and squirrels from the more ponderous noises made by heavier animals.

It was quiet, but not really. Off in the dark pines to the left, a small western squirrel chitted and chatted, dropping shards of pine nut shells to the dry needles below. Further up the mountain, a big red-headed woodpecker thumped his rat-a-tat on a dead pine tree, and a myriad of small birds flitted from tree to tree, making startlingly loud noises.

Strange how they would sound like foot-steps, or antler-twangs, or hide swish, forcing me to glance around, just to make sure. I continued my vigil, now hearing the distant sound of pickup motors, then the bang of truck doors, laughter at an unheard joke and the metallic clack of actions checked. I reflected on the amazing clarity of the sound, knowing that the nearest trail head was the one we started from, a good two hour’s climb away. No wonder the deer had such good warning on “Opening Day.”

A sudden flit of movement 500 to 600 yards off caught my eye, and a small group of deer bounced out of some heavy pines, quickly disappearing in an uphill copse. A modern rifle cracked twice far away, its echo booming around the canyons, followed by the softer thump of a muzzle loader. Somebody whooped down canyon.

A sudden crash and thumping, rhythmic. A deer bounding, on the left. I swung that way, senses alert. A little 2-point bounced into view, angling uphill through my pasture. I let him go. A few more shots sounded in the distance, then again it was quiet. Too quiet. Too warm. The sun angling higher in the Sky. My wool shirt was too hot. Small birds twittered musically and a band of bees droned about. My eyelids drooped. How absolutely delightful.

I dreamed of big bucks. Bucks striding through the sage, with that funny noise of sage on hide and fur. Yipes! My eyes popped open, and the field extending below me blurred into clarity. No buck there, the noise was behind me, uphill. I flopped over. Damn. Too much noise. There he was, staring at me. Big. High, heavy sweep of antlers above his head. I daren’t move, waiting for him to run. Suddenly he turned — and strolled off. I grabbed the chance, swinging the heavy Gemmer around, cocking the hammer at the same time. It sounded like a trip hammer. The buck stopped, and stared hard at me. Somehow I set the DST without pulling off the front trigger, caught him in the sights and touched off the shot.

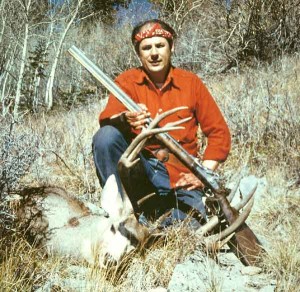

Me and the biggest mule deer I ever killed, barely Boone & Crockett, with the first Gemmer-Springfield that Green River Rifle Works ever made, 45/70 caliber, near the top of Blue Mountqin, which lies just to the west of Monticello, Utah.

Me and the biggest mule deer I ever killed, barely Boone & Crockett, with the first Gemmer-Springfield that Green River Rifle Works ever made, 45/70 caliber, near the top of Blue Mountqin, which lies just to the west of Monticello, Utah.

The fat bullet hit the dirt over his back. I’d missed. No, the buck was humped up, hurt. I set the rifle butt on my toe and reached for my powder horn, then realized I held the ammunition in my left hand. The trapdoor was open in a trice, and new brass dropped into the chamber. This time I took more care, dropping the front sight just a touch, and smacking the lead slug through a front shoulder and into the vitals. The buck collapsed like a sack of spuds and tumbled down hill. End over end he came, finally stopping 20-odd yards in front. And what a buck. Big horns. Fat.

The rest of story is anti-climax. Photos, congratulations, skinning, and gutting. Near half the party took a buck, as did “Runner.” The rest of the day we spent in backbreaking labor getting the meat off “Blue Mountain.” I carefully caped out the big one, carrying out hide and horn as well. He now rests in a place of honor on my wall — just opposite the rack that holds the Gemmer-Springfield.

GRRW’s first Gemmer-Hawken, unfinished, photo taken just after the hunt.

Good Hunting

DOC